译者按

- 长文注意:本译文共计约 1.6 万个汉字。

- 本文有关于手术前后是否应暂停激素治疗的叙述,详见“对血栓的预防”最后一段。

- 为便于阅读及理解,本文对原文个别叙述略有改动(调整排版,或以斜体 标记)。

- 因译者能力所限,部分术语之翻译或有纰漏,烦请指正。

摘要

雌激素可通过激活肝脏雌激素受体、调节各类循环凝血因子的分泌,而增强凝血功能。在雌激素暴露量足够高的情况下,其会引起血栓风险以及与凝血功能有关的心血管并发症(如心肌梗死和卒中)之风险的升高。不过,依雌激素种类、途径与剂量的不同,风险升高的幅度各异。由于非生物同质性雌激素(如炔雌醇)对肝脏代谢的抗性更强,故其在肝脏的表达强度更大,从而比生物同质的雌二醇更易增加血栓风险;而口服雌二醇会经过肝脏的首过效应,其在肝脏的表达强度也高于非口服途径。

在非口服途径下,生理水平的雌二醇所致血栓风险基本为零或极其微弱;而口服雌二醇的风险显著更大,且在高剂量下,会有类似于现代避孕药所含剂量下的炔雌醇的风险。此外,高剂量的非口服雌二醇应当也有不小的血栓与心血管疾病风险,不过该风险应小于含炔雌醇的避孕药。

每单位人口的血栓风险绝对值虽低,但会随时间累加。另外,其它风险因素也会明显助长风险率,包括:年龄、运动量少、与孕激素合用、原因大多不明的血栓形成异常等。

对于女性倾向跨性别者,出于血栓风险更高的考虑,最好应避免使用口服雌二醇与剂量过高的非口服雌二醇——尤其是有相关风险因素者。无论如何,为女性倾向跨性别者作出治疗建议时,不仅要考虑安全性,还应考虑有效性、开销、便利性等其它因素,以及其它替代治疗选项。

前言

雌激素会增强凝血功能并引起血栓(一种心血管疾病)之风险的升高。人体内的血管分为动脉和静脉,其中动脉将血液从心脏带离,而静脉将血液送回心脏;血栓也主要分为两种:静脉血栓或栓塞(VTE)、以及动脉血栓。VTE 还分两种亚型:发生于腿部和骨盆的深静脉血栓(DVT),以及肺血栓(PE)——这种血栓会转移至肺动脉并阻塞之。而动脉血栓会导致心肌梗死(MI;也称心脏病发作)或脑卒中(CVA;俗称中风)。

血栓是很严重的健康问题,其会引起严重并发症乃至死亡。而雌激素在暴露量足够高、从而增强凝血功能的情况下,也有可能引起静脉与动脉血栓、以及上述一系列风险的升高。出于此类潜在健康后果的考虑,血栓风险成为了雌激素使用当中的一项限制因素。

雌激素是雌激素受体(ER)的选择性 激动剂。其被认为可通过激活 ER 而增强凝血功能,从而增加血栓风险。不过,依雌激素类型、用药途径与剂量的不同,其对凝血功能与血栓风险的影响各异。此外,其它因素已知也会影响该风险——包括与孕激素合用,以及一系列激素无关的因素等。

本文旨在对以下方面进行评述:雌激素与血栓风险的关系;雌激素与凝血功能与血栓风险之增长背后的作用机理;以及不同雌激素所引起风险不一的原因。通过探索以上话题,可以揭示为女性倾向跨性别者所用的雌激素剂量应当如何,并有助于尽可能减少风险、提高安全性。

此外,较高的雌激素水平有助于女性倾向跨性别者抑制睾酮产生、但可能使得血栓风险升高,故需要就此分析其利弊。

雌激素与孕激素引起的血栓风险

临床上应用的雌激素种类有很多。其中包括:具备生物同质性的雌激素,如雌二醇;以及非生物同质性雌激素,如结合雌激素(CEE;“倍美力”)、炔雌醇(EE)和己烯雌酚(DES)。雌二醇是人体内主要的天然雌激素。CEE 主要通过释放雌二醇来发挥雌激素效力,不过其也含有数目不小的天然马雌激素,如马烯雌酮(7-去氢雌酮)和 17β-二氢马烯雌酮(7-去氢雌二醇)等。EE 和 DES 皆为人工合成雌激素,并非天然存在;DES 虽已停产数十年,如今鲜为人知,但具有较明显的历史地位。

雌二醇可经口服或非口服形式(如透皮贴片)用药,而非生物同质性雌激素常用于口服。为此,下表列出了以上雌激素在综合雌激素效力上大致等同的剂量。

【表一】 诸雌激素在综合雌激素效力上大致或估计等同的剂量(Aly, 2020; Kuhl, 2005; 表格1; 表格2; 表格3):

| 雌激素类型、途径 | 极低剂量(a) | 低剂量(b) | 中等剂量(b) | 高剂量 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 口服雌二醇 | 1 mg/天 | 2 mg/天 | 4 mg/天 | 8 mg/天 |

| 透皮雌二醇(c) | 25 μg/天 | 50 μg/天 | 100 μg/天 | 200 μg/天 |

| 口服结合雌激素 | 0.625 mg/天 | 1.25 mg/天 | 2.5 mg/天 | 5 mg/天 |

| 口服炔雌醇 | 7.5 μg/天 | 15 μg/天 | 30 μg/天 | 60 μg/天 |

| 口服己烯雌酚 | 0.375 mg/天 | 0.75 mg/天 | 1.5 mg/天 | 3 mg/天 |

| 等效雌二醇水平 | 约 25 pg/mL | 约 50 pg/mL | 约 100 pg/mL | 约 200 pg/mL |

(a) 用于更年期激素替代治疗。

(b) 与绝经前女性在整个月经周期的正常平均/综合雌激素暴露量相当(Aly, 2018)。

(c) 指透皮贴片。

1960 到 1970 年代,雌激素首度被确认与血栓及心血管并发症相关。在临床试验和研究中,以下均被发现会引起上述风险的显著或大幅升高:

- 用于患前列腺癌的男性的高剂量 DES(5 mg/天)(美国退伍军人管理局泌尿学合作研究小组, VACURG, 1967; Byar, 1973; Turo et al., 2014);

- 用于男性预防心脏病的中等剂量 CEE(2.5–5 mg/天)(冠状动脉药物项目研究小组, CDPRG, 1970; CDPRG, 1973; Luria, 1989; Sudhir & Komesaroff, 1999; Dutra et al., 2019);

- 以及早期曾用于绝经前女性的高剂量含 EE 的避孕药(50–150 μg/天)(Gerstman et al., 1991; 美国生殖医学会实践委员会, PCASRM, 2017; 表格)。

男性前列腺癌患者使用 DES 引起的心血管问题相当之大,在整体死亡率上,这实际抵消了其抑制前列腺癌所带来的益处。这些研究的结果给人们敲响了警钟,也引起了对雌激素安全性的担忧;此后,雌激素剂量得以减少。其中,用于治疗前列腺癌的 DES 剂量降至 1–3 mg/天,而避孕药内含的 EE 剂量降至 20–35 μg/天。其它疗法所用雌激素的剂量也有所降低,例如更年期激素治疗。调低剂量虽不能根除用药风险,但有助于降低之。

在美国“女性健康倡议”(WHI)随机对照试验当中,低剂量口服 CEE(0.625 mg/天)单药会引起轻微的血栓风险上升(Anderson et al., 2004; Curb et al., 2006; Prentice & Anderson, 2008; Prentice, 2014; 表格)。此外,当与低剂量醋酸甲羟孕酮(MPA;2.5 mg/天)合用时,该风险还会有显著增长(Rossouw et al., 2002; Cushman et al., 2004; Prentice & Anderson, 2008; Prentice, 2014; 表格)。

另一项大型随机对照试验:心脏与雌激素/人工孕激素补充治疗研究(HERS)也发现,将低剂量 CEE 与低剂量 MPA 合用时会引起血栓风险的升高(Hulley et al., 1998; Grady et al., 2000)。除 MPA 以外,其它孕激素在与口服雌激素合用时,也会助长由后者引起的血栓风险(Rovinski et al., 2018; Scarabin, 2018; Oliver-Williams et al., 2019; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019; 表格)。

有大型观察性研究发现,类似于 CEE,低剂量口服雌二醇(通常 ≤2 mg/天)也与血栓风险的升高有关,增幅取决于剂量(Olié, Canonico, & Scarabin, 2010; Renoux, Dell’Aniello, & Suissa, 2010; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019; Konkle & Sood, 2019; 表格)。不过,口服雌二醇或酯化雌激素的风险应小于口服 CEE(Smith et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2014; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019; 表格)。(酯化雌激素是一种与 CEE 类似的制剂,但马雌激素含量更少。)

另一方面,还有一项大型观察性研究发现,口服雌二醇与口服 CEE 在与孕激素合用时,二者引起的血栓风险增幅相当(Roach et al., 2013)。孕激素与口服雌二醇合用时,也会助长由后者引起的血栓风险,这跟与口服 CEE 合用时类似(Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019; 表格)。

透皮雌二醇的情况与口服雌激素相反:已知其在低至中等剂量(50–100 μg/天)之下,并未引起凝血功能的增强,也未增加血栓及相关心血管并发症的风险(Canonico et al., 2008; Hemelaar et al., 2008; Olié, Canonico, & Scarabin, 2010; Renoux, Dell’Aniello, & Suissa, 2010; Mohammed et al., 2015; Stuenkel et al., 2015; Bezwada, Shaikh, & Misra, 2017; Rovinski et al., 2018; Scarabin, 2018; Konkle & Sood, 2019; Oliver-Williams et al., 2019; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019; Abou-Ismail, Sridhar, & Nayak, 2020; 表格)。

类似地,据“更年期、雌激素与静脉事件研究”(MEVE)发现,当用于有血栓史的女性时,口服雌二醇可引起血栓风险的大幅上升;而透皮雌二醇(平均剂量 50 μg/天)并未引起该风险的上升(Olié et al., 2011)。

然而,有几项关于透皮雌二醇与心血管风险的例外;例如,一项观察性研究发现,较高剂量(>50 μg/天)的透皮雌二醇贴片用于更年期女性时,会引起卒中风险的增长(Renoux et al., 2010; Oliver-Williams et al., 2019);有的研究还发现,口服和透皮雌二醇对女性倾向跨性别者凝血功能的影响差异很小以至无差异(Lim et al., 2020; Scheres et al., 2021)。

对于更年期所用剂量下的透皮雌二醇与孕激素合用时是否与更高的血栓风险相关这一问题,现有研究的结论五花八门;有的未发现任何差异,有的则发现风险有所上升(Rovinski et al., 2018; Scarabin, 2018; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019)。有人曾表示,这应该与所用孕激素类型有关(Scarabin, 2018)。

关于口服或透皮雌二醇在高于更年期激素疗法所用的剂量下对血栓风险的影响,至今仍鲜有高质量临床资料发表。无论如何,用于女性化激素疗法的口服雌二醇(如 2–8 mg/天;通常还与抗雄激素制剂、孕激素等其它药品合用)所引起的血栓风险已得到较有限的评价。此类研究所披露的血栓风险增幅,要高于更年期激素疗法所用较低剂量下的口服雌二醇(Wierckx et al., 2013; Weinand & Safer, 2015; Arnold et al., 2016; Getahun et al., 2018; Irwig, 2018; Connelly et al., 2019; Connors & Middeldorp, 2019; Goldstein et al., 2019; Iwamoto et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019; Konkle & Sood, 2019; Quinton, 2019; Swee, Javaid, & Quinton, 2019; Abou-Ismail, Sridhar, & Nayak, 2020)。

尽管 WHI 已披露口服 CEE 单药治疗与血栓风险的因果关系,但对于口服或透皮雌二醇单药治疗与血栓风险的因果关系,目前尚无任何随机对照试验能够给出具备足够统计学强度的结论。由于血栓很罕见,只有大规模、且高支出的试验项目方可呈现这类数据,但至今没有任何这样的研究进行过。同样地,对于含 EE 的避孕药与血栓风险之升高的关系,至今亦无任何随机对照试验开展过(Moores, Bilello, & Murin, 2004)。

无论如何,在其它情况下,雌激素已被明确表明与此存在因果关系;该结论也可类推至口服雌二醇。

另外,有一项随机对照试验:“雌激素及静脉血栓影响试验”(EVTET),在曾有血栓史的已绝经女性当中分别使用低剂量口服雌二醇(2 mg/天)合并醋酸炔诺酮(NETA;一种孕激素)、以及安慰剂;结果表明,该激素配方引起了凝血功能与血栓发生率的显著升高——试验组、对照组发生率分别为 10.7% 和 2.3%(P = 0.04)(Høibraaten et al., 2000; Høibraaten et al., 2001)。

绝经前女性体内的雌二醇水平与血栓风险基本无关(Holmegard et al., 2014)。这里要指出一项事实:更年期女性使用 100 μg/天的透皮雌二醇贴片,并未引起更大的血栓风险;因为此剂量平均可达到 100 pg/mL 的雌二醇水平,这与绝经前女性正常月经周期内的综合平均水平相当(Aly, 2018; 维基百科)。

当异常激素状态(如妊娠与服用避孕药)得到控制之后,无论是女性还是男性(男性的雌二醇水平通常很低),都会有相近的血栓发生率(Moores, Bilello, & Murin, 2004; Rosendaal, 2005; Montagnana et al., 2010; Roach et al., 2013)。不过耐人寻味的是,男性复发血栓的几率总是高于女性(Roach et al., 2013)。

上述结果表明,绝经前女性生理水平下的雌二醇与孕酮,基本上不会使凝血功能或血栓风险明显升高。不过,现有资料有反面例子:有的研究指出生理范围内的雌二醇、孕酮水平其实会影响到绝经前和/或围绝经期女性的凝血功能(Chaireti et al., 2013)以及血栓风险(Simon et al., 2006; Canonico et al., 2014; Scheres et al., 2019)。

现代复方避孕药含有中等剂量的 EE(20–35 μg/天)和一种生理剂量的孕激素。其可将血栓风险提高数倍之多(Konkle & Sood, 2019; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2015; 表格)。此外,其还会将心肌梗死与卒中风险提高约 1.5–2 倍(Lidegaard, 2014; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。不过,避孕药并未引起整体死亡率的升高——至少对服用该药的较年轻女性而言(Hannaford et al., 2010)。

依据关于更年期激素治疗的研究,此类避孕药中的孕激素会助长由 EE 引起的血栓风险。早年使用的避孕药(含高剂量 EE,即 50–100 μg/天)所引起的血栓风险,可达现代避孕药的两倍之高(Gerstman et al., 1991; PCASRM, 2017; 表格)。

而非口服形式的含 EE 避孕制剂(如透皮避孕贴片和阴道避孕环等)所引起的血栓风险,和口服避孕药相似;这与口服和透皮雌二醇之间的风险有别的情况截然相反(Plu-Bureau et al., 2013; PCASRM, 2017; Konkle & Sood, 2019; Abou-Ismail, Sridhar, & Nayak, 2020)。因此,根据现有资料,EE 的给药途径并不会改变血栓风险,这与雌二醇不同。

已知在用于乳腺癌或前列腺癌病人的高剂量雌激素疗法中运用口服人工雌激素(如 DES 和 EE),会引起血栓及心血管并发症风险的剧烈升高(Phillips et al., 2014; Turo et al., 2014; Coelingh-Bennink et al., 2017)。另外,已知将磷酸雌莫司汀(EMP,一种雌二醇酯)以大剂量用于治疗前列腺癌(如口服 140–1,400 mg/天,足可引起妊娠时雌二醇水平),亦出现了类似现象(Kitamura, 2001 [图表]; Ravery et al., 2011)。

不过有 1980 年代的研究发现,高剂量非口服雌二醇所引起的心血管风险,并不等同于高剂量口服人工雌激素或 EMP 的风险(von Schoultz et al., 1989; Ockrim & Abel, 2009);其中包括针对聚磷酸雌二醇(PEP;一种注射用长效雌二醇前体)、以及高剂量透皮雌二醇凝胶的研究(von Schoultz et al., 1989; Aly, 2019)。

然而,后续规模更大、质量更佳的研究发现,尽管 PEP 引起的心血管风险远低于高剂量口服人工雌激素,但仍有所增长(Hedlung et al., 2008; Ockrim & Abel, 2009; Hedlund et al., 2011; Sam, 2020);其中,在雌二醇水平大致达 300–500 pg/mL 之范围内的情况下,血栓风险会增长约两倍(Sam, 2020)。

而迄今采用高剂量透皮雌二醇贴片的研究,则未发现心血管并发症有大幅增长(Langley et al., 2013; Sam, 2020)。不过,这些研究仍较缺乏统计学强度支撑,从而使其解释不大有力。无论如何,已观察到高剂量透皮贴片在使雌二醇水平达到 350–500 pg/mL 的情况下引起了凝血功能增强,这与 PEP 相似(Bland et al., 2005; Mikkola et al., 1999)。

目前在英国有两项正评价高剂量雌二醇透皮贴片用于前列腺癌的大型临床研究:前列腺癌透皮激素疗法研究(PATCH)与晚期、转移期前列腺癌系统性治疗用药有效性评价研究(STAMPEDE),其未来有望提供更多关于该雌二醇形式与血栓、心血管风险的资料(Gilbert et al., 2018; Singla, Ghandour, & Raj, 2019)。

还需留意注射用短效雌二醇酯(如戊酸雌二醇、环戊丙酸雌二醇)的情况:其常为女性倾向跨性别者所用,且常用剂量可引起较高雌二醇水平。和高剂量雌二醇透皮贴片的情况类似,目前鲜少或尚未有关于这类注射剂与血栓风险的高质量资料。

Pyra 及其同行发现,戊酸雌二醇注射剂用于女性倾向跨性别者时,可将血栓风险提高约 2 倍,但结果置信区间极大,不具备统计显著性(Pyra et al., 2020)。实验群体所用剂量不明;但据称对于 VTE 患者,所用戊酸雌二醇剂量介于每周一次 4–20 mg 和每两周一次 10–40 mg 之间(Pyra et al., 2020)。

其它研究也对此有所评价,并发现高剂量戊酸雌二醇注射剂(每两周一次 10–40 mg)用于男性前列腺癌患者时,会引起凝血功能增强(Kohli & McClellan, 2001; Kohli et al., 2004; Kohli, 2005)。

还观察到用于绝经前女性的、含 5 mg 戊酸雌二醇和一种孕激素的注射用复方避孕药(每月一次),也引起了凝血功能增强(Meng et al., 1990; UN/WHO et al., 2003)。

对于短效雌二醇注射剂所引起的雌二醇水平尖峰,是否会对凝血功能及血栓风险有害这一问题,目前尚不明朗(Hembree et al., 2017)。不过,鉴于注射用短效睾酮酯所引起的红细胞增多症风险要高于其它非口服睾酮(Ohlander, Varghese, & Pastuszak, 2018),可以间接推论,以上观点可能属实。与此对应,有一项研究发现,使用相同剂量的注射用复方避孕药时,含戊酸雌二醇者会引起凝血功能增强,含环戊丙酸雌二醇者却不会(后者作用时间更长、且有更稳定的雌二醇水平)(UN/WHO et al., 2003)。

与雌激素相似,诸如他莫昔芬、雷洛昔芬等选择性雌激素受体调节剂(SERM),也会使血栓风险升高(Park & Jordan, 2002; Fabian & Kimler, 2005)。该风险增幅可达数倍,接近于中等剂量口服雌二醇或 CEE 的预估风险(Deitcher & Gomes, 2004; Iqbal et al., 2012; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。

妊娠期间,体内雌二醇与孕酮会激增至极高水平(图表)。其中,雌二醇水平在妊娠期间会逐渐升高,在妊娠前期、中期和后期结束时平均分别达 2,000 pg/mL、10,000 pg/mL 和 20,000 pg/mL 左右(Kerlan et al., 1994 [图表]; Schock et al., 2016)。凝血功能在妊娠期间大幅增强,血栓风险也随之剧烈升高(Heit et al., 2000; Abdul Sultan et al., 2015; Heit, Spencer, & White, 2016; 表格)。妊娠期间的雌二醇与孕酮水平与凝血功能增强呈强相关性(Bagot et al., 2019)。

由现代避孕药引起的血栓风险,总体上和妊娠相近(Heit, Spencer, & White, 2016);而早年曾用的含高剂量 EE 的避孕药、以及用于乳腺癌与前列腺癌的高剂量口服人工雌激素治疗所引起的风险增长,则与妊娠后期相似。

另外,在刺激绝经前女性排卵以进行体外受精的过程中,其体内雌二醇也会升至相当高的水平;已知这也与凝血功能及血栓风险之升高有关(Westerlund et al., 2012; Rova, Passmark, & Lindqvist, 2012; Kasum et al., 2014)。

由于存在心血管健康风险更高等诸多疑虑,DES 事实上已被弃用;而 EE 也不再用于除避孕以外的一切适应症。之所以 EE 还用于避孕,是因为其对子宫的代谢作用有抗性,其控制月经出血的能力亦优于口服雌二醇(Stanczyk, Archer, & Bhavnani, 2013)。至于 CEE,尽管医学上仍较多用于顺性别女性的激素治疗,但也正逐渐为雌二醇所取代。

此外,透皮雌二醇也大有取代口服雌二醇用于更年期激素治疗之势。

目前主流的跨性别激素治疗指南(另见 Aly, 2020)不建议将 EE 与 CEE 用于女性倾向跨性别者,理由是风险更大、且血清雌激素水平无法准确监测(Coleman et al., 2012; Deutsch, 2016; Hembree et al., 2017)。如今雌二醇是女性倾向跨性别者使用的几乎唯一一种雌激素。

除雌激素类型外,这些指南还建议年龄高于 40–45 岁、或者有血栓风险的女性倾向跨性别者应以透皮雌二醇取代口服使用(Deutsch, 2016; Iwamoto et al., 2019; Glintborg et al., 2021)。

现有关于更年期激素治疗的指南,同样建议有较高血栓风险的顺性别女性使用透皮雌二醇、而非口服(例如 Stuenkel et al., 2015)。

如上文所述,孕激素会助长口服雌激素引起的血栓风险。但相反的是,关于非口服雌二醇与孕激素合用的研究结果众说纷纭——有的发现风险升高了,有的则未发现额外风险(Rovinski et al., 2018; Scarabin, 2018; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019)。

孕激素本身通常不会增强凝血功能(Kuhl, 1996; Schindler, 2003; Wiegratz & Kuhl, 2006; Sitruk-Ware & Nath, 2011; Sitruk-Ware & Nath, 2013; Skouby & Sidelmann, 2018),也不会提高血栓风险(Blanco-Molina et al., 2012; Mantha et al., 2012; Tepper et al., 2016; Rott, 2019)。不过有一项特例:避孕剂量下的注射用 MPA 可将血栓风险提高数倍(van Hylckama Vlieg, Helmerhorst, & Rosendaal, 2010; DeLoughery, 2011; Blanco-Molina et al., 2012; Gourdy et al., 2012; Mantha et al., 2012; Rott, 2019; Tepper et al., 2019)。其原因尚不明确,不过可能与该注射剂引起的较高 MPA 水平峰值(Mantha et al., 2012)、或者 MPA 的弱糖皮质激素活性有关(Kuhl & Stevenson, 2006; Sitruk-Ware & Nath, 2011)。

除生理剂量的 MPA 单药之外,已知高剂量 MPA、醋酸甲地孕酮(MGA)和醋酸环丙孕酮(CPA)也和凝血功能增强、血栓风险升高有关(Schröder & Radlmaier, 2002; Schindler, 2003; Seaman et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2013; Taylor & Pendleton, 2016)。然而,有一项小型研究将醋酸氯地孕酮(CMA)用于曾有血栓史的女性,发现 CMA 的情况并非同样如此(Conard et al., 2004)。

如将 CPA 与雌激素一并用于女性倾向跨性别者,其也会引起血栓风险增长(Patel et al., 2022)。

口服孕酮的情况与人工孕激素制剂相反:在雌激素治疗中加入口服孕酮,并不会助长血栓风险(Scarabin, 2018; Oliver-Williams et al., 2019; Kaemmle et al., 2022)。不过这也许只是出于口服孕酮仅可产生很低的孕酮水平、且孕激素效力很弱这一事实的缘故罢了(Aly, 2018)。非口服、效力完全的孕酮的情况尚未被充分研究,故其风险仍未可知(Aly, 2018)。

有件历史研究值得一提:研究系荷兰阿姆斯特丹自由大学医学中心(VUMC)的性别焦虑专家中心(CEGD)于 1980 年代开展的,其中在血栓风险上,服用高剂量 EE 与 CPA 的女性倾向跨性别者比一般人群预期值高了 45 倍之多(Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989; Asscheman et al., 2014);而其它风险也一并升高,甚至死亡率也更高了(Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989; Gooren & T’Sjoen, 2018)。

CEGD 后来针对女性倾向跨性别者开展的一项研究,证实了 EE 会极大增强凝血功能,但口服或透皮雌二醇仅些微增强之(Toorians et al., 2003)。当 CEGD 决定以生理剂量的口服或透皮雌二醇(还常与 CPA 合并)取代高剂量 EE 用于女性倾向跨性别者之后,该风险得到显著降低(van Kesteren et al., 1997; Asscheman et al., 2011; Asscheman et al., 2014)。

这些结果极大促进了在女性化激素治疗当中以雌二醇取代 EE 的过程;其也无疑极大增长了对高剂量雌激素用于女性倾向跨性别者的顾忌。

综上所述,已知各类雌激素均会提高血栓风险、或与之存在关联,强度取决于剂量。上述结果表明,只要暴露量足够大,雌激素无疑都会引起凝血功能和血栓风险升高。然而,相比于雌二醇,非生物同质性的人工雌激素皆会有更高血栓风险;而口服雌二醇的风险亦高于非口服。

事实上,在女性生理水平下的雌二醇,或低至中等剂量下的透皮雌二醇,可能不具备明显的血栓风险。尽管如此,只要暴露量足够高,非口服雌二醇同样可引起一定的血栓风险升高。

孕激素在与雌激素合用时,基本都会助长由后者引起的血栓风险,在高剂量下尤其明显。

不同激素暴露量引起的风险

下表显示了不同类型、途径、剂量下的雌激素,以及 SERM、妊娠和高剂量 CPA 所引起的相对风险率。其中可见风险更高的情况:

- 口服雌二醇相对于非口服雌二醇;

- 非生物同质性雌激素相对于雌二醇;

- 高雌激素剂量、水平相对于低雌激素剂量、水平。

【表二】 不同激素暴露量所引起的血栓相对风险率(另见 Machin & Ragni, 2020):

| 雌激素 | 血栓风险率 | 数据来源 |

|---|---|---|

| 口服雌二醇 ≤1 mg/天 | 1.2 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 口服雌二醇 >1 mg/天(1) | 1.4 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 口服雌二醇 ≤1 或 >1 mg/天(1) + 孕激素(2) | 1.4–1.8 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 透皮雌二醇 ≤50 μg/天 | 0.9 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 透皮雌二醇 >50 μg/天(1) | 1.1 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 口服 CEE ≤0.625 mg/天 | 1.4 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 口服 CEE >0.625 mg/天(1) | 1.7 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 口服 CEE ≤ 或 >0.625 mg/天(1) + 孕激素(2) | 1.5–2.4 倍 | Vinogradova et al. (2019) [表格] |

| 现代避孕药(EE + 孕激素)(3) | 4.2 倍 | Heit, Spencer, & White (2016) |

| 早期避孕药(高剂量 EE + 孕激素)(3) | 4–10 倍(4) | Tchaikovski, Tans, & Rosing (2006); PCASRM (2017) [表格] |

| 高剂量聚磷酸雌二醇注射剂(5) | 2.1 倍 | Sam (2020) |

| 高剂量口服 DES、EE 或 EMP | 5.7–10 倍 | Seaman et al. (2007); Ravery et al. (2011); Klil-Drori et al. (2015) |

| SERM(他莫昔芬、雷洛昔芬) | 约 1.5–3 倍 | Deitcher & Gomes (2004); Iqbal et al.(2012); Konkle & Sood (2019) |

| 妊娠(整体风险)(6) | 4.0 倍 | Heit, Spencer, & White (2016) |

| 妊娠(后期) | 5.1–7.1 倍 | Abdul Sultan et al. (2015) [表格] |

| 高剂量 CPA 单药 | 3–5 倍 | Seaman et al. (2007) |

(1) 在用于更年期激素替代的通常剂量下(不会很高;或不高于所示剂量的两倍)。

(2) 以下其中一种:醋酸甲羟孕酮、炔诺酮、炔诺孕酮或屈螺酮。

(3) 现代避孕药含有 20–35 μg/天的炔雌醇,而早期避孕药(1960–1970 年代所用)则含有 50–150 μg/天。

(4) 该风险率可达现代避孕药的约两倍之高。

(5) 来自本站未正式发表的原创研究/分析文章,结果几乎具备统计显著性(95% CI 0.99–4.22)。

(6) 不包括产褥期。如一并计入,则妊娠引起的血栓风险率为 5–10 倍(McLintock, 2014)。

需要指出,上表所列各值大多来自诸观察性研究的相关量,而非随机对照试验。因此,对于某些情况,因果关系尚未完全确立。此外,由于 95% 置信区间很大,以上各值多仅代表粗略的平均值。因此,以上估算值的准确性在某些情况下可能较差。

还需指出,因定义及方法的差异,不同研究对血栓风险的量化可能有别(其成因包括采样误差、对混杂变量的控制手段、以及残余混杂因子的影响等)。

雌激素对凝血功能的增强之机理

雌激素受体(ER)在肝脏内表达,而雌激素通过激活受体而在肝脏发挥效力(Eisenfeld & Aten, 1979; Eisenfeld & Aten, 1987; Sahlin & von Schoultz, 1999; Grossmann et al., 2019)。雌激素被认为可通过激活肝脏内的 ER、调节多种凝血因子(包括促凝因子和抗凝因子)在肝脏的产生,而增加血栓风险(Kuhl, 2005; Tchaikovski & Rosing, 2010; DeLoughery, 2011; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。

大多数凝血因子及其抑制物由肝脏合成(Mammen, 1992; Amitrano et al., 2002; Peck-Radosavljevic, 2007);随后被分泌至血液,进入体内循环并介导各自效力。

雌激素可影响以下凝血因子的循环水平(Hemelaar et al., 2008; Doxufils, Morimont, & Bouvy, 2020):

- 促凝因子,包括

- 抗凝因子,包括

- 纤维蛋白溶解因子,包括

- 血纤维蛋白溶酶原(纤溶酶原);

- 组织纤溶酶原激活剂(t-PA);

- 纤溶酶原激活剂抑制物-1(PAI-1)。

对净凝血活性标志物(如凝血酶原片段 1.2、D-二聚体、凝血酶—抗凝血酶复合物等)以及全身凝血功能测定(如基于凝血酶生成潜力的活性 C 蛋白抗性试验)的评价显示,由雌激素引起的血清因子水平变动,会导致整体促凝作用的加强(口服避孕药与凝血功能研究小组, 1999; Kohli, 2006; Hemelaar et al., 2008; Douxfils et al., 2020; Douxfils, Morimont, & Bouvy, 2020)。

大多数由雌激素引起的凝血因子水平之变动相对较小,且通常仍维持于正常范围内。不过,放到一起的话,它们对全身凝血功能与血栓风险的增长作用会更大(Douxfils et al., 2020; Douxfils, Morimont, & Bouvy, 2020; Reda et al., 2020)。

除凝血因子外,雌激素还调节多种肝脏产物的合成(Kuhl, 1999; Kuhl, 2005; 表格)。其中包括:

与雌激素引起凝血功能与血栓风险升高背后的机理一样,不同类型及途径的雌激素在对雌激素敏感的肝脏产物上的影响之差异,和对血栓风险的影响之差异完全一致。也就是说,不同雌激素在肝脏和在体内其它部位的效力差别,是有所不同的。

非生物同质性的人工雌激素对肝脏合成的影响,要高于雌二醇;而口服雌二醇的影响要高于非口服途径(如透皮和肌肉注射)。这可能解释了为何这些雌激素对凝血功能与血栓风险的影响不一。

下表显示了不同雌激素暴露量对肝脏的效力;其中测定的是 SHBG 水平,其为受雌激素调节的肝脏产物当中最敏感、且特征明显的一种。

【表三】 不同雌激素暴露量所引起的 SHBG 水平相对增长率(另见 Aly, 2020):

| 雌激素 | SHBG 增幅 | 数据来源 |

|---|---|---|

| 雌二醇贴片 50 μg/天 | 1.1 倍 | Kuhl (2005) |

| 雌二醇贴片 100 μg/天 | 1.2 倍 | Shifren et al. (2008) |

| 口服雌二醇 1 mg/天 | 1.6 倍 | Kuhl (1998) |

| 口服雌二醇 2 mg/天 | 2.2 倍 | Kuhl (1998) |

| 口服雌二醇 4 mg/天 | 1.9–3.2 倍 | Fåhraeus & Larsson-Cohn (1982); Gibney et al. (2005); Ropponen et al. (2005) |

| 口服 EV 6 mg/天(1) (等效雌二醇约 4.5 mg/天) | 2.5–3.0 倍 | Dittrich et al. (2005); Mueller et al. (2005); Mueller et al. (2006) |

| 口服 CEE 0.625 mg/天 | 1.8 倍 | Kuhl (1998) |

| 口服 CEE 1.25 mg/天 | 2.2 倍 | Kuhl (1998) |

| 口服 EE 5 μg/天 | 2.0 倍 | Kuhl (1999) |

| 口服 EE 10 μg/天 | 3.0 倍 | Kuhl (1998) |

| 口服 EE 20 μg/天 | 3.4 倍 | Kuhl (1998) |

| 口服 EE 50 μg/天 | 4.0 倍 | Kuhl (1997) |

| 现代避孕药(含 EE 与孕激素)(2) | 约 3.0–4.0 倍 | Odlind et al. (2002) |

| 早期避孕药(含高剂量 EE 与孕激素)(2) | 约 5–10 倍 | Hammond (2017) |

| 雌二醇贴片 200 μg/天 | 约 1.5 倍 | Smith et al. (2019) |

| 雌二醇贴片 300 μg/天 | 约 1.7 倍 | Smith et al. (2019) |

| 雌二醇贴片 600 μg/天 | 约 2.3 倍 | Bland et al. (2005) |

| 高剂量雌二醇注射剂(3) | 1.7–3.2 倍 | Stege et al. (1988); Kronawitter et al. (2009) 表格; Mueller et al. (2011); Nelson et al. (2016) |

| 高剂量口服 DES、EE 或 EMP | 约 5–10 倍 | von Schoultz et al. (1989) |

| 妊娠 | 约 5–10 倍 | Hammond (2017) |

(1) 因分子量有别,戊酸雌二醇所含雌二醇占其质量的约 75%。因此,6 mg/天的戊酸雌二醇大致等效于 4.5 mg/天的雌二醇。

(2) 现代避孕药含有 20–35 μg/天的炔雌醇,而早期避孕药(1960–1970 年代所用)则含有 50–150 μg/天。

(3) 注射 320 mg/月的 PEP(雌二醇水平约 700 pg/mL)、100 mg/月的十一酸雌二醇(雌二醇水平约 500–600 pg/mL)或 10 mg/十天的 EV(雌二醇水平峰值约 500–1200 pg/mL;图表)。

雌激素治疗所引起的 SHBG 水平升高,与凝血功能及血栓风险的上升是同时发生的,故可视作此类效应的一种可靠的替代指标(Odlind et al., 2002; van Rooijen et al., 2004; van Vliet et al., 2005; Tchaikovski & Rosing, 2010; Raps et al., 2012; Stegeman et al., 2013; Hugon-Rodin et al., 2017; Eilertsen et al., 2019)。

某些情况下,SHBG 水平的增幅甚至还与血栓风险之增幅非常接近;例如,服用现代避孕药(皆提高约 4 倍)、服用高剂量口服人工雌激素(皆提高 ~5–10 倍)以及妊娠后期(皆提高约 5–10 倍)。

尽管目前有关特定雌激素途径或剂量所致血栓风险的资料还较缺乏以至不存在(例如高剂量口服雌二醇、或者高剂量注射用雌二醇酯);但借由观察 SHBG 水平的变动,可以粗略推断对肝脏总的影响、凝血系统变化的幅度,以及血栓风险。

不过需要注意,孕激素在与雌激素合用时,会助长后者的血栓风险,同时不一定会影响 SHBG 水平,有的甚至因伴有雄激素活性而降低 SHBG 水平(Kuhl, 2005; Vinogradova, Coupland, & Hippisley-Cox, 2019)。

生理水平下的雌二醇对肝脏合成的影响基本上较微弱(Eisenfeld & Aten, 1979; Lax, 1987; Kuhl, 2005);这与其在女性当中仅有轻微、以至没有血栓风险的认识相一致。目前认为,在正常生理条件下,雌二醇应当仅在相当高的水平下——即妊娠期间——才会明显影响肝脏合成。妊娠期间肝脏产物的变化可能会起到重要的生物作用(Eisenfeld & Aten, 1979);凝血功能被认为是其中之一,因为凝血功能可减少分娩时的失血,从而有助于 (产妇) 存活。

相反的是,除妊娠之外,凝血功能的增强并不会带来任何明显益处。

口服雌二醇与肝脏首过效应

药物经口服后需首先从肝门静脉经过肝脏,即首过效应;而非口服 途径的药物不会先经过肝脏(Pond & Tozer, 1984; Back & Rogers, 1987)。因此,口服雌二醇会受肝脏首过效应影响,但非口服形式(如透皮、注射)的雌二醇则不会(Kuhl, 1998; Kuhl, 2005)。

首过效应会导致雌二醇在肝脏的暴露量、以及其对肝脏蛋白合成的雌激素作用畸高(Kuhl, 2005)。类似地,口服雌二醇对肝脏凝血因子合成的雌激素作用同样畸高(Kuhl, 1998; Kuhl, 2005)。据估计,受首过效应影响,口服雌二醇对肝脏的雌激素作用强度是非口服雌二醇的 4–5 倍(Kuhl, 2005)。

从观察性研究已发现透皮雌二醇的血栓风险较口服更低;由于大多数非口服途径可避免肝脏首过效应,这点应相当符合生物学逻辑(Baber et al., 2016)。

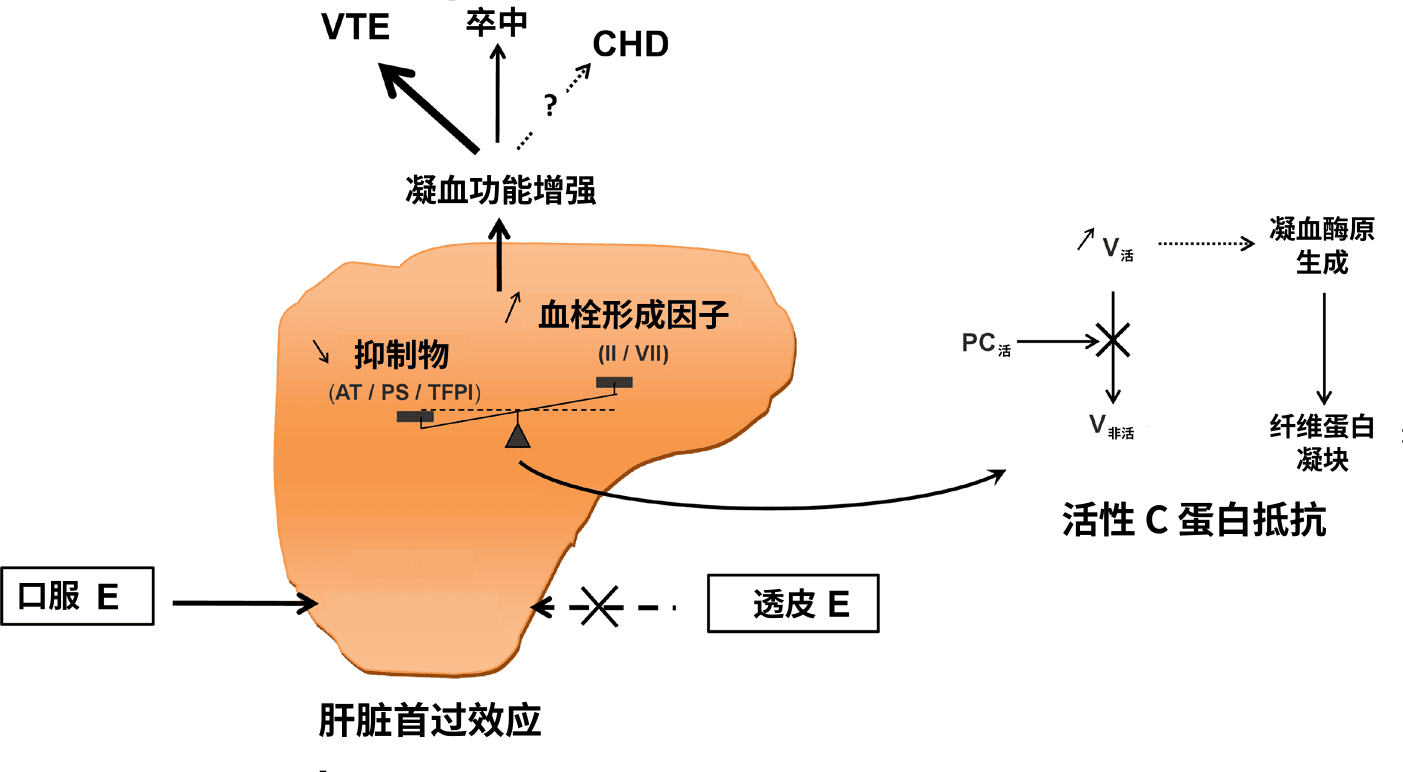

【图一】 口服雌激素经肝脏首过效应引起凝血功能增强的示意图(Scarabin et al., 2020)。缩写:

- E——雌激素;

- AT——抗凝血酶;

- PS——S 蛋白;

- TFPI——组织因子途径抑制物;

- II——凝血酶原;

- VII——凝血因子 VII;

- PC——C 蛋白;

- V——凝血因子 V;

- VTE——静脉血栓;

- CHD——冠心病。

另见词条“活性 C 蛋白抵抗”(APCR)。

尽管由于首过效应,口服雌二醇引起血栓的可能性远远更高;但只要雌二醇水平足够高,无论何种给药途径的雌二醇,都会扩散至肝脏并发挥效力。因此,非口服途径(或自身分泌)引起的高雌二醇水平也会像口服一样,引起凝血功能与血栓风险的升高。这点可从雌激素效力极高的一些情况明确证实,例如妊娠及刺激排卵以供体外受精的情况——此时雌二醇水平升至极高,会显著影响肝脏蛋白的合成。

非生物同质性雌激素与肝脏代谢抵抗

诸如 EE、DES 和 CEE 等非生物同质性雌激素,对肝脏蛋白的合成以及血栓风险之影响,不仅大于口服雌二醇,也高于非口服雌二醇(Kuhl, 1998; Kuhl, 2005; Phillips et al., 2014; Turo et al., 2014; 表格)。这是因为,雌二醇会被肝脏剧烈代谢并失活,而非生物同质性雌激素在分子结构上有别于雌二醇,使得其具有远高于雌二醇的肝脏代谢抗性(Kuhl, 1998; Kuhl, 2005; Connors & Middeldorp, 2019; Swee, Javaid, & Quinton, 2019)。

以 EE 为例:其口服生物利用度约为 45%,而口服雌二醇仅有约 5%(Kuhl, 2005; Stanczyk, Archer, & Bhavnani, 2013)。此外,EE 的血浆清除半衰期长达 5–30 小时,而雌二醇仅有不足 1 小时(White et al., 1998; Kuhl, 2005; Stanczyk, Archer, & Bhavnani, 2013)。从总和雌激素效力来看,包括前述在内的一系列差别,使得同质量下 EE 之效力相当于雌二醇的约 120 倍(Kuhl, 2005; 表格)。因此,临床上 EE 的剂量以微克计,而口服雌二醇的剂量要以毫克计、且高出 100 倍以上。

EE 与雌二醇在药代动力学上的差别可以反映出 EE 对肝脏代谢的高度抗性(Kuhl, 2005)。之所以 EE(也称 17α-乙炔雌二醇)具备对肝脏代谢的抗性,是因为其在碳 17α 点位上比雌二醇多出了一个乙炔基团(Kuhl, 2005);这种分子修饰导致了位阻效应,即其阻止了 17β-羟甾体脱氢酶(17β-HSD)、以及硫酸基转移酶和葡萄糖醛酸基转移酶等结合酶作用于碳 17β 点位上的羟基团,从而阻止对 EE 的代谢。其中,17β-HSD 通常将雌二醇转化为活性较弱的雌酮,而结合酶会将雌二醇转化为无活性的 17β-硫酸或葡萄糖醛酸雌激素结合物(如硫酸雌酮)(Kuhl, 2005)。

事实上,类似于“乙炔雌酮”的代谢物是完全不存在的;因为其需要在第 17 碳原子上以两个分子键与氧原子结合 为酮基团——而结合点位只有 C17α 与 C17β,前者在 EE 分子内已由乙炔基团占有。因此,EE 不像雌二醇那样会在肝脏内代谢成效力较弱或无活性的物质(如雌酮与硫酸雌酮),以防止激活肝脏受体、增强凝血功能;其也因此与更高的血栓风险有关(Kuhl, 2005; Russell et al., 2017)。

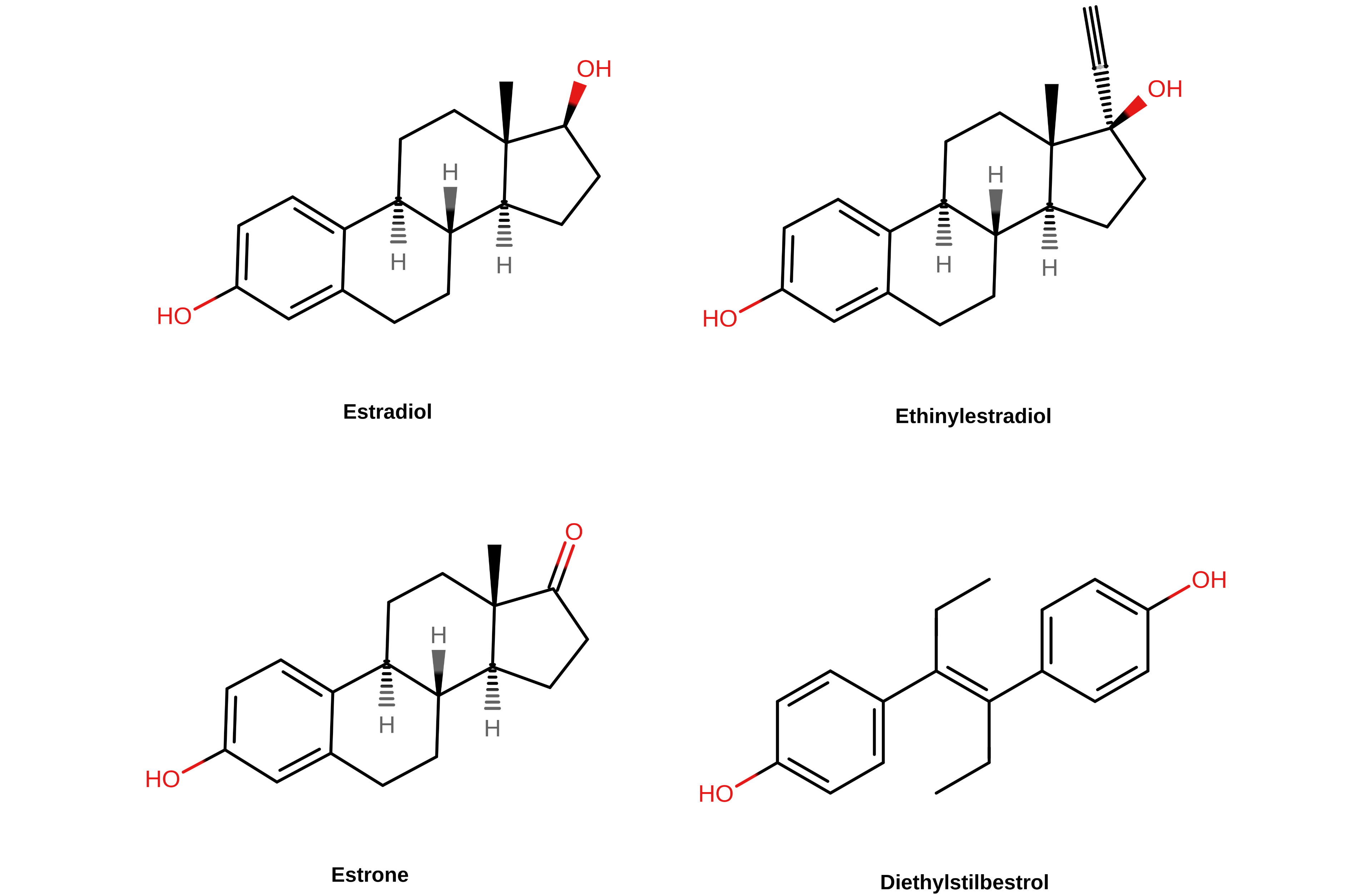

【图二】 几种雌激素的化学结构。甾体雌激素(雌二醇、炔雌醇与雌酮)的第 17 碳原子位于其结构式的右上角。

译者注: 左上起分别为雌二醇、炔雌醇、雌酮、己烯雌酚。

由于 EE 对肝脏代谢与失活机制有明显抗性,故可在肝脏内维持很长时间;其裂解之前往往会多次循环经过肝脏。此外,相比于等效剂量的口服雌二醇,EE 对肝脏蛋白合成作用的畸高程度要高出好几倍(Kuhl, 2005; 表格)。从而,EE 不仅在总和效力上比口服雌二醇高约 120 倍,更是在对肝脏的效力上高出约 350–1,500 倍(von Schoultz et al., 1989; Kuhl, 2005)。即使剂量低至 1 μg/天,EE 仍会对肝脏代谢造成影响(Speroff et al., 1996; Trémollieres, 2012)。

还有,无论是经口服、还是经透皮或阴道给药,EE 皆会对肝脏与血栓风险产生相似的影响;该事实表明,EE 无需经过口服的首过效应便可影响血栓风险,这点与口服雌二醇不同(Plu-Bureau et al., 2013; PCASRM, 2017; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。EE 的代谢抗性很高,这意味着无论何种途径,都对肝脏有显著影响。

EE 在肝脏的超强效力,使得其对凝血功能与血栓风险的影响远甚于等效剂量下的雌二醇。

CEE 对肝脏蛋白合成作用的畸高程度,也高于口服雌二醇数倍,但低于 EE(Kuhl, 2005; 表格)。这可能与其含有的马雌激素有关;马雌激素并不为人体接受,也对人肝脏代谢存在抗性。

另一方面,DES 对肝脏的雌激素作用则更甚于 EE(Kuhl, 2005; 表格)。之所以 DES 对肝脏合成的影响畸高程度还高于 EE 或 CEE,可能是因为 DES 是一种非甾体类雌激素,在结构上相较甾体雌激素精简了许多。这点应该有一定关系,因为 DES 不像甾体雌激素对肝脏甾体代谢酶有不同程度的敏感性(Kuhl, 2005),其对 17β-HSD 无亲和性,故其羟基团也不会被氧化,成为形如雌酮的酮基代谢物;这点和 EE 类似(Jensen et al., 2010)。

由于具有高于雌二醇的肝脏代谢抗性,在等效剂量下,CEE 及非甾体类雌激素 DES 等也与 EE 一样,对凝血功能与血栓风险具有更大影响(不过影响程度不一)。

如将口服非生物同质性雌激素与透皮(而非口服)雌二醇作比较,其对受雌激素调节的肝脏蛋白合成之影响就犹如天壤之别了。只需简略计算,便很快得知为何此类雌激素在高剂量下会有类似于妊娠的、对肝脏蛋白及血栓风险的影响。下表显示了经粗略估算的、不同雌激素对肝脏的相对作用强度。

【表四】 雌激素对肝脏的雌激素效力及总体/全身雌激素效力之比值,由特定肝脏产物(如 SHBG)粗略估算而来(Kuhl, 2005; 表格):

| 雌激素 | 相比口服雌二醇的肝脏效力 | 相比透皮雌二醇的肝脏效力 |

|---|---|---|

| 透皮雌二醇 | 约 0.25 倍(1) | 1.0 倍(1) |

| 口服雌二醇 | 1.0 倍 | 约 4.0 倍 |

| 口服结合雌激素 | 1.3–4.5 倍 | 约 5.2–18 倍 |

| 口服炔雌醇 | 2.9–5.0 倍 | 约 12–20 倍 |

| 口服己烯雌酚 | 5.7–7.5 倍 | 约 23–30 倍 |

(1) 基于一项研究的结果:在可达到同等雌二醇水平的剂量下,口服雌二醇对 SHBG 水平的影响相当于透皮雌二醇的 4 倍(Nachtigall et al., 2000)。

由雌激素引起的肝脏蛋白合成之变化,并非与剂量或对肝脏相对效力呈线性关系。其中,SHBG 及其它肝脏产物的水平会随雌激素剂量上升,并逐渐达到饱和——也即,高剂量的影响并没有低剂量下那么大(Kuhl, 1990; Kuhl, 1999)。例如,口服 EE 在 5 μg/天、10 μg/天、20 μg/天与 50 μg/天的剂量下,引起 SHBG 水平上升的幅度分别为 2.0 倍、3.0 倍、3.4 倍和 4.0 倍(Kuhl, 1998; Kuhl, 1999)。此结果可归因于高雌激素浓度对肝脏 ER 的竞争性结合、激活趋于饱和(Kuhl, 1990)。

有一点可以印证之:尽管口服 EE 对肝脏的效力远甚于口服雌二醇,但后者可能会意外地很快“后来居上”,超过 EE 及其它非生物同质性雌激素。相应地,已知口服雌二醇在 1 mg/天、2 mg/天与 4 mg/天剂量下,引起的 SHBG 水平增幅分别为 1.6 倍、2.2 倍和 1.9–3.2 倍(Fåhraeus & Larsson-Cohn, 1982; Kuhl, 1998; Gibney et al., 2005; Ropponen et al., 2005)。

因此,尽管口服 EE 对肝脏的效力可达口服雌二醇的约 3–5 倍,但在总和雌激素效力接近于 EE 的剂量下,口服雌二醇也足以引起较大的 SHBG 水平增长,增幅仅仅略低于 EE。

选择性雌激素受体调节剂及其代谢抗性

SERM 是雌激素受体(ER)的部分激动剂,包括他莫昔芬、雷洛昔芬等。这与雌激素不同——像雌二醇、CEE、EE 和 DES 之类都是 ER 的完全激动剂。

与 DES 等非甾体雌激素类似,临床应用的 SERM 均属于非甾体物质,对肝脏代谢有高度抗性。事实上,像他莫昔芬与氯米芬等特定类型的 SERM,在分子结构上与 DES 很接近,也是 DES 的衍生物。

SERM 在不同组织内有不同的雌激素调节作用;其在骨骼等一些组织会发挥雌激素效力,而在乳房等其它组织发挥抗雌激素效力(Lain, 2019; 表格)。尽管不同 SERM 对特定组织(如子宫)的效力各异,但其皆在肝脏表达雌激素效力;因此,SERM 也会像雌激素一样提高血栓风险(Park & Jordan, 2002; Fabian & Kimler, 2005)。与非生物同质性雌激素类似,SERM 引起血栓风险的增幅也高于口服雌二醇,其原因亦可归于对肝脏更高的代谢抗性、以及更强的雌激素效力。

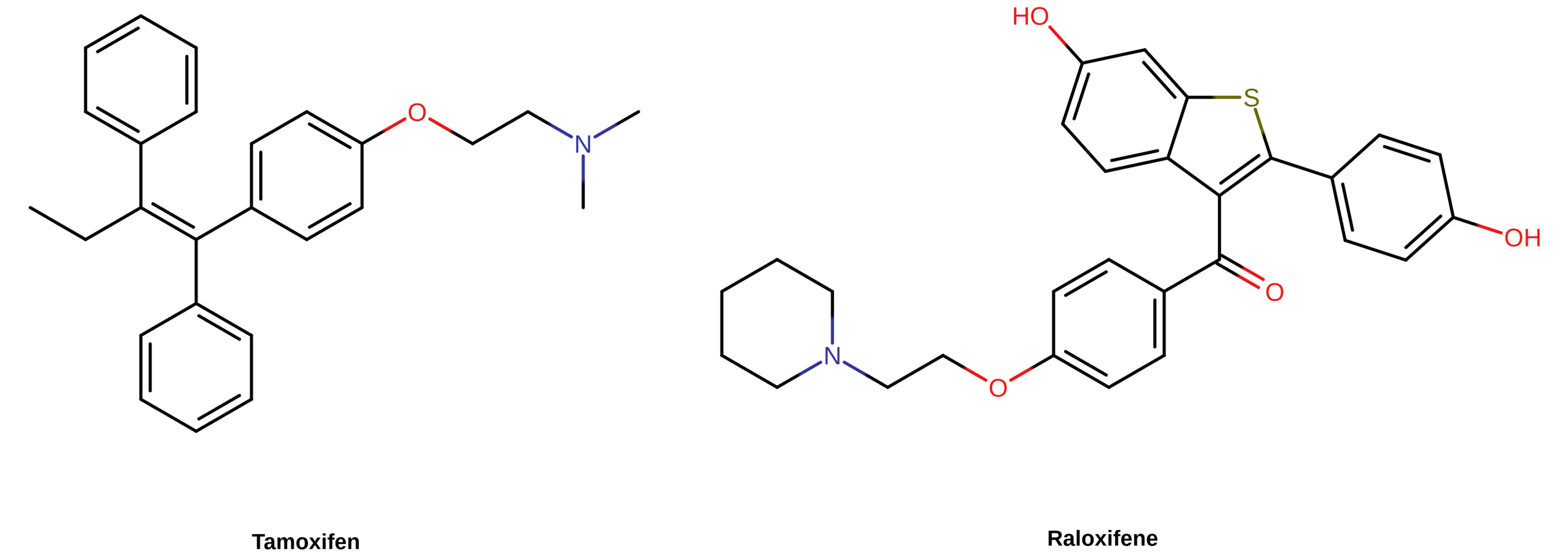

医学上使用的 SERM 可分为多种结构类型;例如他莫昔芬属于三苯乙烯类,而雷洛昔芬属于苯并噻吩类。不同结构类型的 SERM 之间只有一项共同点:就是其与 ER 的互动机制相似。

【图三】 部分 SERM 的化学结构。其在结构上均属于非甾体物质,其中包括他莫昔芬(左,三苯乙烯类)与雷洛昔芬(右,苯并噻吩类)。

雌激素与 SERM 对雌激素受体的激活:凝血功能增强的缘由

来自临床前基因研究的结果,直接证明了血栓风险之升高源自 ER 的激活。有一项重要的动物研究,对小鼠服用 EE 后的促凝及抗凝生物标志物的变化进行了测定;其发现 EE 引起了多种凝血因子水平的变化(Cleuren et al., 2010)。研究者还评估了服用雌二醇的情况,也发现了类似变化(Cleuren et al., 2010)。如将 EE 与一种选择性 ER 完全拮抗剂:氟维司群合用,则后者会完全中和由 EE 诱发的凝血变化(Cleuren et al., 2010)。此外,在已敲除雌激素受体 α 的小鼠中使用 EE,则未对凝血因子产生影响(Cleuren et al., 2010)。

上述发现与对人及小鼠的全基因组关联分析所发现的一致——即雌激素响应元件(ERE)在涉及凝血通路的大量基因当中广泛存在(Cleuren et al., 2010; Stanczyk, Mathews, & Cortessis, 2017)。(ERE 是一段位于基因转录起点的 DNA 序列,受 ER 调控而与转录因子结合,从而起到调控这些基因的作用。——译者注)

以上结果恰恰表明,之所以雌激素会引起凝血功能与血栓风险升高,就是因为 ER 的激活。其也印证了一项事实:各类选择性 ER 激动剂无论在化学结构上有多大差别,皆会引起血栓风险;其还间接证明了某些非 ER 引起的效应并非凝血功能增强的起因(例如雌酮作为弱雌激素活性的代谢物,会在一定程度上与雌二醇共同引起血栓风险—Bagot et al., 2010)。

因此,凝血功能与血栓风险的升高可视为雌激素与 SERM 的共同作用——在肝脏暴露量足够高的情况下。不过,不同类型的 ER 激动剂对肝脏代谢的敏感度不同,从而对凝血功能具有不同的影响。

由于雌二醇对肝脏代谢缺乏抗性,也会在肝脏内大量失活,故其引起凝血功能与血栓风险升高所需的剂量(尤其是非口服雌二醇),要高于非生物同质性雌激素。故此,如用于雌激素治疗,雌二醇(尤其非口服途径)会比其它雌激素更安全。

血栓绝对发生率与风险因素

对女性而言,雌激素、孕激素暴露量状态(例如极高的激素摄入,或者妊娠)无疑是公认的血栓风险因素。不过,在无相关风险因素的年轻健康人群当中,即使因激素引起血栓风险的极大提升,也极少出现血栓病例(Rosendaal, 2005)。

非妊娠期女性的年化 VTE 绝对发生率,仅为每万人 1–5 例(即年均 0.01–0.05%)(PCASRM, 2017; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。而当女性服用含 EE 的避孕药时,尽管其 VTE 风险平均会提高约 4 倍,但年化 VTE 发生率仅有每万人 3–9 例(即年均 0.03–0.09%)(Konkle & Sood, 2019)。类似地,女性妊娠期间,尽管雌二醇与孕酮水平变得极高,VTE 风险也升高了至多 7 倍(Abdul Sultan et al., 2015),但血栓绝对发生率仅有每年每万人约 5–20 例(即年均 0.05–0.2%)(PCASRM, 2017; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。

【表五】 绝经前女性在不同雌激素暴露量下的 VTE 绝对发生率(Gerstman et al., 1991; Konkle & Sood, 2019; Douxfils, Morimont, & Bouvy, 2020):

| 组别/疗法 | 年均发生率 |

|---|---|

| 非妊娠期女性 各年龄段(Rabe et al., 2011): | 每万人 1–5 例(0.01–0.05%) |

| ⚫ 不足 19 岁 | 每万人 1–2 例 |

| ⚫ 20–29 岁 | 每万人 2–3 例 |

| ⚫ 30–39 岁 | 每万人 3–4 例 |

| ⚫ 40–49 岁 | 每万人 5–7 例 |

| ⚫ 15–49 岁平均 | 每万人约 3–4 例 |

| 现代避孕药(EE <50 μg/天) | 每万人 3–12 例(0.03–0.12 %)(注) |

| 早期避孕药(EE >50 μg/天) | 每万人约 10 例(0.1%) |

| 妊娠期 | 每万人 5–20 例(0.05–0.2%) |

| 产褥期 | 每万人 40–65 例(0.4–0.65%) |

(译者注) 已更正,原文为“0.03–0.09%”

无论如何,高雌激素暴露量引起的 VTE 及心血管风险,会随时间及人口规模累积。据估计,欧洲每年发生 22,000 例由避孕药引起的 VTE 病例(Morimont, Dogné, & Douxfils, 2020);在美国,每年有 300–400 名年轻健康女性死于由避孕药引起的血栓(Keenan, Kerr, & Duane, 2019)。

需要指出,如将避孕药改为含有雌二醇或雌四醇、而非 EE,则会显著减小促凝作用、降低血栓风险;如果这点得到进一步证实,将有望大幅减少血栓病例(Stanczyk, Archer, & Bhavnani, 2013; Dinger, Minh, & Heinemann, 2016; Grandi, Facchinetti, & Bitzer, 2017; Fruzzetti & Cagnacci, 2018; Grandi et al., 2019; Grandi et al., 2020; Douxfils, Morimont, & Bouvy, 2020; Reda et al., 2020; Morimont et al., 2021; Grandi, Facchinetti, Bitzer, 2022)。

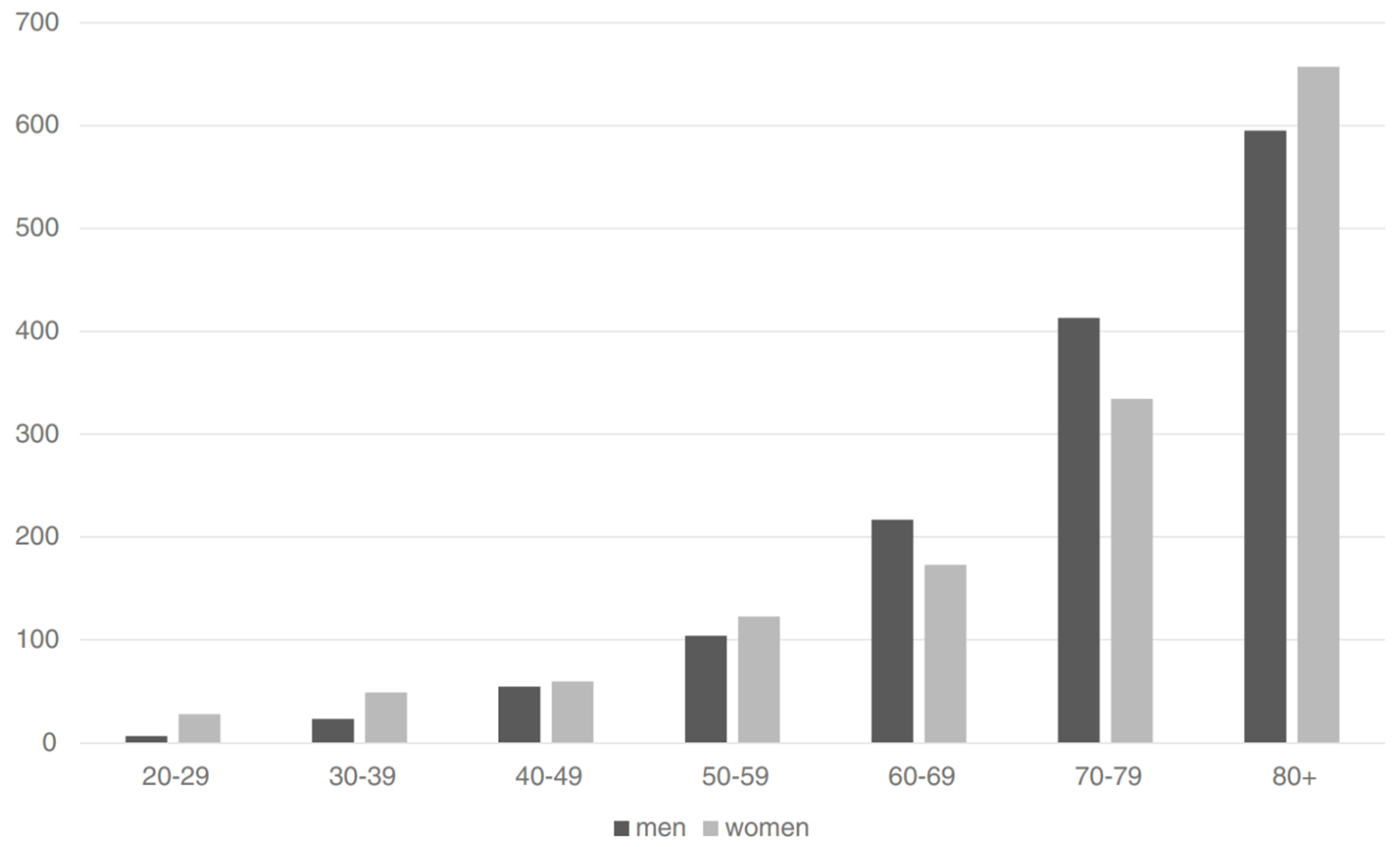

已知除雌激素与孕激素暴露量之外,也有一系列引起血栓风险的其它因素,其会与时间和人口规模一道明显助推风险率(Heit et al., 2000; Rosendaal, 2005)。其中,年龄是已知最主要的风险因素之一(Rosendaal, 2005; Montagnana et al., 2010)。年龄也是最特别的一项因素,因为每个人都会逐渐与此相关。血栓风险率在 15 岁以下的人群中仅有年均 <0.005–0.01%;而到了 80 岁以上,该风险率升至年均约 0.5–1.0%,增长一百倍左右(Rosendaal, 2005; Montagnana et al., 2010; Rabe et al., 2011)。

下图将年龄对血栓风险的影响可视化展现。

【图四】 在不同年龄段,每十万名男性(黑色柱)及女性(灰色柱)首次发生 VTE 的年均风险率(Oger, 2000; Rosendaal, 2005; Rosendaal, 2016)。

引起血栓及心血管问题的其它已知风险因素包括:运动量少(例如卧床、长途旅行等),肥胖,吸烟,凝血指标异常,癌症,外科手术,艾滋病,等等(Baron et al., 1998; Heit et al., 2000; Rosendaal, 2005; Lijfering, Rosendaal, & Cannegieter, 2010; Timp et al., 2013)。

除年龄之外,运动量少也是最主要的血栓风险因素之一,也会助推许多其它因素引起的风险(Oger, 2000; Rosendaal, 2005; Rosendaal, 2016)。

吸烟本身并不大会引起 VTE 风险的增长(Lijfering, Rosendaal, & Cannegieter, 2010);但如同时服用含 EE 的避孕药,也会一并提高 VTE 风险(Pomp, Rosendaal, & Doggen, 2008),同时还大幅提高心肌梗死风险——例如,老烟民患心梗的风险会提高 20 倍(Kuhl, 1999)。

下表显示了一些已知风险因素对 VTE 的影响:

【表六】 除激素过量以外的其它 VTE 风险因素,以及 VTE 风险相对增幅(Baron et al., 1998; Heit et al., 2000; Rosendaal, 2005; Lijfering, Rosendaal, & Cannegieter, 2010; Timp et al., 2013):

| 风险因素 | 相对风险率 |

|---|---|

| 年龄 | 1 倍到无穷大 |

| 癌症 | 2–20 倍(1) |

| 艾滋病 | 3–10 倍 |

| 超重、肥胖 | 2–3 倍 |

| 外科手术、创伤、行动能力丧失 | 5–50 倍 |

| 在家卧床不动 | 9 倍 |

| 乘坐飞机 | 1.5–3 倍 |

| 吸烟 | 0.8–1.5 倍(2) |

| 静脉曲张 | 1–4 倍 |

| 妊娠 | 4 倍 |

| 产褥期 | 15–20 倍 |

(1) 视类型与阶段而不同(Baron et al., 1998; Timp et al., 2013)。据一项研究的结果,乳腺癌与前列腺癌分别使 VTE 风险增至一般人群的 1.8 倍与 4.2 倍(Baron et al., 1998)。

(2) 吸烟本身并非必然和 VTE 有关(Lijfering, Rosendaal, & Cannegieter, 2010; Rabe et al., 2011)。

遗传性与获得性易栓症,在人群中占比不小,且会导致血栓风险大幅增长(Lijfering, Rosendaal, & Cannegieter, 2010)。其也很少被人察觉(Morimont, Dogné, & Douxfils, 2020)。这是因为,对遗传性易栓症的筛查多基于家族病史,在识别有相关异常的人群时,这不仅难以感知,且很难作出预警(Morimont, Dogné, & Douxfils, 2020)。故此,许多人正处在高血栓风险而不自知。

下表显示了一系列凝血指标异常的流行率,以及其对血栓风险的影响。

【表七】 凝血指标异常的流行率,及 VTE 相对风险率(Martinelli, Passamonti, & Bucciarelli, 2014; Mannucci & Franchini, 2015; 另见 Walker, 2009; Konkle & Sood, 2019)。

| 易栓症类型 | 一般人群流行率 | VTE 患者流行率 | VTE 首次发病 风险率 | VTE 复发 风险率 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 抗凝血酶缺乏 | 0.02–0.2% | 1% | 50 倍 | 2.5 倍 |

| C 蛋白缺乏 | 0.2–0.4% | 3% | 15 倍 | 2.5 倍 |

| S 蛋白缺乏 | 0.03–0.1% | 2% | 10 倍 | 2.5 倍 |

| 凝血因子 V 的 Leiden 突变(杂合型) | 5% | 20% | 7 倍 | 1.5 倍 |

| 凝血因子 V 的 Leiden 突变(纯合型) | 0.02% | 1.5% | 80 倍 | – |

| 凝血酶原 G20210A 突变(杂合型) | 2% | 6% | 3–4 倍 | 1.5 倍 |

| 凝血酶原 G20210A 突变(纯合型) | 0.02% | 小于 1% | 30 倍 | – |

| 非 O 型血人群 | 55–57% | 75% | 2 倍 | 2 倍 |

| 抗磷脂抗体 | 1–2% | 5–15% | 11 倍 | ? |

| 高同型半胱氨酸血症 | 5% | 10–15% | 1.5 倍 | ? |

血栓被视为一种多成因的疾病(Rosendaal, 2005)。当多种风险因素并存时,激素暴露量对血栓及心血管并发症风险的影响是最大的。在最极端的情况之一下——即高龄、有癌症、同时还在服用高剂量人工雌激素(如 DES)——,血栓发生率可高达 15–28%,而心血管并发症的总体发生率可高达 35%(Phillips et al., 2014; Sciarria et al., 2014; Turo et al., 2014)。

上述不良反应让这些人群的发病率和死亡率都有很大增加。不过,绝大多数人远未达到如此高的风险。像是,妊娠期女性在其雌二醇与孕酮水平已极高的同时,仍仅有微小的血栓问题,是因为年龄所致;又如,老年癌症患者接受高剂量人工雌激素治疗,却有很高的死亡风险,这也是年龄作梗。

由 VUMC 开展的研究发现,女性倾向跨性别者使用高剂量 EE 与 CPA 长达 5–10 年之后,其血栓发生率增长了 20–45 倍;VUMC 于 1989 年的报道和 1997 年的跟踪报道指出的血栓绝对发生率,分别为 6.3% 和 5.5%(每年每万人 142 例和 58 例)(Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989; van Kesteren et al., 1997; Asscheman et al., 2014; Goldstein et al., 2019; Min & Hopkins, 2021)。

而据 1989 年研究报道,年龄低于 40 岁和高于 40 岁的人群之绝对发生率,则为 2.1% 和 12%;这与目前关于年龄对血栓风险之影响的认识相吻合(Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989; Asscheman et al., 2014)。有约 70% 的病例除年龄以外无任何查明的血栓风险因素(Asscheman, Gooren, & Eklund, 1989; Asscheman et al., 2014)。当以低至中等剂量的透皮雌二醇取代 EE 用于年龄逾 40 岁的人群之后,其血栓发生率显著降低了(该群体内仅出现一例血栓病例)(van Kesteren et al., 1997; Asscheman et al., 2014; Min & Hopkins, 2021)。

后来,由比利时根特大学附属医院于 2013 年开展的一项研究发现,治疗时长平均达 7.7 年(范围从 3 个月到 35 年不等)的女性倾向跨性别者群体的血栓发生率为 5.1%;其用药主要为雌二醇(口服或透皮)、合并或不合并 CPA(Wierckx et al., 2013) Min & Hopkins, 2021)。患血栓的人群大多有诸如高年龄、吸烟、因手术失去行动能力或处于凝血增强状态等风险因素(Wierckx et al., 2013) Min & Hopkins, 2021)。

除(激素)累计暴露时间之外,以上研究还揭示了多种风险因素并存会对血栓风险有何等影响;这些因素包括雌激素类型、途径和剂量,孕激素暴露量,以及年龄,等等。

对女性倾向跨性别者的治疗意义

非生物同质性雌激素(如 EE 与 CEE)因有更高的血栓和心血管健康风险,如今已几乎不再为女性倾向跨性别者所用;取而代之的是口服与非口服形式的雌二醇。目前通行的跨性别临床指南一般都推荐,无论使用口服、还是非口服途径的雌二醇,皆应将雌二醇水平维持在非妊娠期女性的正常生理范围内,即 100–200 pg/mL 左右(Aly, 2018)。

至于高于此范围的雌二醇水平,目前尚未证实其在女性化或乳房发育等方面具备更好的疗效(Nolan & Cheung, 2020)。不过,当雌二醇水平处于较高的 200–500 pg/mL 范围内时,其还可有效抑制睾酮——如先前女性化效果不够充分,如此或可起到间接促进作用(Aly, 2018)。

如使用雌二醇酯注射剂,在现有跨性别临床指南所推荐的剂量下,其引起的雌二醇水平可达到以至大幅超出其推荐要维持的生理水平之上限:200 pg/mL(Aly, 2021)。

基于现有研究的结果(例如低剂量下或同等 SHBG 增幅下的血栓风险),高剂量口服雌二醇(如 8 mg/天)在血栓风险上的表现若与含较少 EE 的避孕药相似,也不会令人意外。与孕激素(如 CPA)合用时,风险还会变得更高。由于口服雌二醇相比非口服途径具有更大、且不必要的风险,故最好避免用于女性倾向跨性别者——尤其是有血栓相关风险因素者(如年龄 >40 岁),以及与孕激素合用者。不过,口服雌二醇具有便利性较好、开销较少等显著优点;女性倾向跨性别者及其医师(在用药选择上)也会将其纳入考虑。

非口服雌二醇的情况与口服相反:在维持生理范围(即 100–200 pg/mL)的雌二醇水平的同时,其仅会有微弱、以至不会有血栓风险。因此,生理水平下的非口服雌二醇可安全用于女性倾向跨性别者。

而某些非口服雌二醇会引起超生理的水平;据估计,300–500 pg/mL 左右的雌二醇水平可将血栓水平升高 2 倍(Sam, 2020),而这仍低于由正广泛使用的含 EE 避孕药引起的平均 4 倍之多的风险增长。鉴于如此高的雌二醇水平有助于抑制睾酮分泌,且此类避孕药在全球正广泛为顺性别女性所用,可以认为,高剂量(合理范围内)的非口服雌二醇所引起的血栓风险率在女性倾向跨性别者当中应该足可容忍(Haupt et al., 2020);尤其是将高剂量非口服雌二醇单药治疗与雌二醇、抗雄制剂联合治疗(如雌二醇合并螺内酯、CPA 或比卡鲁胺等——皆有各自的风险及缺点)进行比较之后,更会凸显前者的优越性。

无论如何,与口服雌二醇的理由类似,使用非口服雌二醇时,最好也应避免引起较高的雌二醇水平,因为其也会表现出更大的风险;尤其是对于有血栓相关风险因素者(如年龄较高)。此外,使用超高剂量、且已超过抑制睾酮所需的非口服雌二醇,是很难站得住脚的;因为其会徒增不必要的风险,亦无任何额外益处。

对血栓的预防

预防血栓的最好方式,是避免引来任何风险。从这点而言,如果可行、且希望选用更安全的治疗方案,则可推荐避免使用口服雌二醇、过高剂量的非口服雌二醇,以及孕激素。此外,对于有相关风险因素者(如年龄超 40 岁)、凝血指标异常者、以及有久坐习惯者,则更提倡避免使用以上方案。

积极运动(如步行及健身)、戒烟、减肥等,皆有助于减小血栓风险(Hibbs, 2008)。

某些抗凝药物及抗血小板药物可用于高风险人群,避免其发生血栓。例如:

- 低剂量的阿司匹林(Mekaj, Daci, & Mekaj, 2015; Matharu et al., 2020);

- 凝血因子 Xa 直接抑制剂,如利伐沙班(品牌 Xarelto)(Blondon, 2020);

- 凝血酶直接抑制剂,如达比加群(品牌 Pradaxa);

- 等等。

已知阿司匹林可有效预防血栓(Mekaj, Daci, & Mekaj, 2015; Matharu et al., 2020),也有人建议将其用于正接受激素治疗的女性倾向跨性别者(Feldman & Goldberg, 2006; Deutsch, 2016)。不过,关于预防由激素治疗引起的血栓之证据仍较有限,且存在争议(Grady et al., 2000; Cushman et al., 2004);不建议将阿司匹林用于女性倾向跨性别者以预防血栓的也大有人在(Shatzel, Connelly, & DeLoughery, 2017)。

已知利伐沙班不仅可中和由更年期口服激素治疗引起的血栓风险,且有过之而无不及(Blondon, 2020)。

无论如何,目前尚无任何抗凝药物被批准或支持用于预防激素疗法引起的血栓风险。有鉴于此,现有临床指南表示,目前已有证据尚不足以为这方面的抉择提供指引(例如 McLintock, 2014)。

还需注意,抗凝药物也有各自的副作用及风险,应当谨慎使用。

在跨性别社区当中,有人推荐将芦丁用于预防血栓,且声称得到了有限的临床前研究支持(Jasuja et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2015)。(芦丁是一种天然的黄酮苷,见于多种植物与食物,并以草本保健品的形式在售。)

不过,目前尚无任何临床证据对此用法或其效力予以支持(Martinez-Zapata et al., 2016; Morling et al., 2018);也尚未开展剂量范围研究来确立其有效剂量。

此外,已知芦丁等黄酮苷在体内会有诸多不良性质(例如生物利用度很低、代谢率高、半衰期短),因此其生物活性很弱、且疗效不佳,使得其用处有限(Ma et al., 2014; Higdon et al., 2016; Cassidy & Minihane, 2017; Zhao, Yang, & Xie, 2019; Zhang et al., 2021)。

最后,芦丁的耐受性及安全性尚未得到评估。出于上述原因,目前不应建议女性倾向跨性别者为降低血栓风险而服用芦丁。

传统认为,手术前暂停雌激素的服用有助于减小术后恢复期的血栓风险,故建议、指示用于即将接受手术的女性倾向跨性别者(例如 Asscheman et al., 2014)。然而,目前关于此法尚缺乏有力的证据支持;仍需更多研究来确认其是否真的会有益处(Boskey, Taghinia, & Ganor, 2019; Nolan & Cheung, 2020; Haveles et al., 2021; Hontscharuk et al., 2021; Kozato et al., 2021; Nolan et al., 2021; Zucker, Reisman, & Safer, 2021)。

近期开展的研究并未发现女性倾向跨性别者术前停用激素会使血栓风险降低;但其统计学强度不足,尚需更大规模的研究以佐证之(Blasdel et al., 2021)。

暂停服用激素对某些女性倾向跨性别者而言会很痛苦,为此要相应做出权衡。有一种办法可作为替代,就是短期使用生理剂量的透皮雌二醇;其不会引起血栓风险,应更为安全。

后记

后记一:Langley 等人 (2021) PATCH 研究成果

2021 年二月,一篇有关前列腺癌透皮激素治疗(PATCH)试验引起的长期心血管结局的报道被公开发表(Langley et al., 2021; PDF 文档; 补充附录)。PATCH 是正在开展的一项大型二期/三期随机对照试验,其将高剂量雌二醇透皮贴片和 GnRH 激动剂用于治疗男性前列腺癌的情况进行对比(Langley et al., 2021)。其中所用雌二醇贴片的剂量,为 3–4 片 100 μg/天;品牌来自 FemSeven 或 Progynova TS(Langley et al., 2021)。

据 2021 年二月报道所述,有 1,694 名男性参与试验并被随机分配,其中 790 人服用 GnRH 激动剂,904 人使用雌二醇贴片(Langley et al., 2021)。

在上述雌二醇剂量下,雌二醇水平中值约达 215 pg/mL(5%–95% 范围:~100–550 pg/mL)(Langley et al., 2021)。雌二醇贴片组男性有约 93% 的睾酮水平被抑制到去势范围内(<50 ng/dL),这与 GnRH 激动剂组的抑制率相一致(约 93%)(Langley et al., 2021)。然而,该报道虽有睾酮抑制率,却未提供实际睾酮水平,因此这两组之间无法进行比较(Langley et al., 2021)。

在平均约 4 年的跟踪时长之后,雌二醇组与 GnRH 激动剂组的多项心血管结局并无明显差异;其中包括 VTE、血栓栓塞性卒中及其它动脉栓塞事件(Langley et al., 2021)。此结果与早前有关 PEP 用于前列腺癌的大型临床研究结果截然相反;后者发现心血管发病率与 VTE 风险皆有所上升,但其中雌二醇水平明显高于 PATCH 试验(Ockrim & Abel, 2009; Sam, 2020)。

PATCH 的研究者从其颇具吸引力的用药安全性资料出发,表示治疗前列腺癌时应重新考虑采用透皮雌激素(Langley et al., 2021)。

上述发现令人安心,其表明将雌二醇水平控制在有限的较高范围(像 200–300 pg/mL 这样)之时,其对女性倾向跨性别者的血栓及心血管风险应该也足够安全。

然而应当指出,这项试验当中的样本规模尽管大于早前的同类临床研究,但用来评价血栓风险还不够充分;血栓发生率极低,需要很大的样本规模方可完全量化之。例如,有的研究对围绝经期及已绝经女性的血栓风险作了精确评价,而其受试者规模多达数万人。因此,尽管从该试验可知风险率并未显著上升,但当下也不能排除有小幅上升的可能。

还需指出,该研究所用剂量引起的较强睾酮抑制效力,并不代表在女性倾向跨性别者身上也会出现;因为该研究的受试者大多已步入老年,且睾酮水平会随年龄增长而降低。

后记二:Totaro 等人 (2021) 与 Kotamarti 等人 (2021) 所作论文

2021 年十一月,一项有关女性化激素疗法引起的血栓风险的系统性回顾、荟萃分析兼回归分析研究被公开发表:

- Totaro, M., Palazzi, S., Castellini, C., Parisi, A., D’Amato, F., Tienforti, D., Baroni, M. G., Francavilla, S., & Barbonetti, A. (2021).

Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Transgender People Undergoing Hormone Feminizing Therapy: A Prevalence Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Study. [一项流行率荟萃分析兼回归分析研究:关于正接受女性化激素治疗的跨性别者的静脉血栓风险]

Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 741866. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2021.741866]

该项目是迄今同类研究当中规模最大的一个。该荟萃分析囊括了来自 18 项研究的总计 11,542 名正接受激素治疗的女性倾向跨性别者。其中,VTE 的总流行率为 2%(95% 置信区间:1–3%)。然而,不同研究之间存在很大的差异。

该荟萃分析发现,高年龄与更长的激素治疗年限,皆与 VTE 流行率呈显著正相关。年龄达 37.5 岁及以上的人群当中,VTE 流行率为 3%(95% CI:0–5%);反过来,当年龄小于 37.5 岁时,VTE 流行率则为 0%(95% CI:0–2%)。

激素治疗年限达 4.4 年及以上的人群当中,VTE 流行率为 1%(95% CI:0–3%);而治疗年限不足 4.4 年者则为 0%(95% CI:0–3%)。

这个 0% 估计值并不意味着其完全没有 VTE 风险,但可以认为此风险率足够低,以至于这次荟萃分析的样本规模还不足以探测并量化之。

该荟萃分析存在一项局限性:其声称,由于数据不足,其未能也无法基于雌激素类型(如雌二醇、CEE 与 EE 的比较)与途径(如口服雌激素或口服雌二醇,和透皮雌二醇的比较)进行亚组分析。

然而,有另一项近期的荟萃分析,不仅也引用了 Totaro 等人 (2021) 所分析文献的大部分,而且确实进行了对诸雌激素类型及途径的亚组分析;其论文于 2021 年七月被公开发表:

- Kotamarti, V. S., Greige, N., Heiman, A. J., Patel, A., & Ricci, J. A. (2021).

Risk for Venous Thromboembolism in Transgender Patients Undergoing Cross-Sex Hormone Treatment: A Systematic Review. [一次系统性评述:关于正接受跨性别激素治疗的跨性别者的静脉血栓风险]

The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(7), 1280–1291. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.04.006]

以下是他们关于对诸雌激素类型及途径的亚组分析的叙述:

由于已有人报道不同雌激素配方具有不同的 VTE 发生率,故在此对口服或透皮给药途径、或者特定雌激素剂型在 VTE 发生率上的差异进行了分析。考虑到有多项研究所报道的受试者的用药系多种雌激素剂型的组合、或者未披露雌激素处方,故本文无法进行进一步的统计分析。

在 AMAB(出生指派性别为男)的人群当中,雌激素的给药途径有一定作用:(口服)雌二醇的 VTE 发生率,为每年每万人 34.0 例(来自 7 项研究);透皮雌激素的 VTE 发生率,则为每年每万人 11.2 例(来自 3 项研究)。此外,不同雌激素剂型也应有不同的 VTE 发生率。

炔雌醇也与 VTE 发生率的升高有关,为每年每万人 293.1 例(来自 3 项研究);其次是结合马雌激素,发生率为每年每万人 49.0 例(来自 1 项研究);最后是戊酸雌二醇,发生率为每年每万人 31.5 例(来自 4 项研究)。

由于所引用研究的数据质量参差不齐,尚不清楚以上计算值的准确度如何。而且,抗雄激素制剂(如 CPA)这个因素并未得到控制,据本文所述,其有可能会对 VTE 风险产生额外影响。无论如何,以上数值很有参考意义,也与不同雌激素类型及途径在 VTE 风险上的不同之处相吻合。

参考文献

- Abdul Sultan, A., West, J., Stephansson, O., Grainge, M. J., Tata, L. J., Fleming, K. M., Humes, D., & Ludvigsson, J. F. (2015). Defining venous thromboembolism and measuring its incidence using Swedish health registries: a nationwide pregnancy cohort study. BMJ Open, 5(11), e008864. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008864]

- Abou-Ismail, M. Y., Citla Sridhar, D., & Nayak, L. (2020). Estrogen and thrombosis: A bench to bedside review. Thrombosis Research, 192, 40–51. [DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.008]

- Amitrano, L., Guardascione, M. A., Brancaccio, V., & Balzano, A. (2002). Coagulation Disorders in Liver Disease. Seminars in Liver Disease, 22(1), 83–96. [DOI:10.1055/s-2002-23205]

- Anderson et al. (2004). Effects of Conjugated Equine Estrogen in Postmenopausal Women With Hysterectomy. JAMA, 291(14), 1701–1712. [DOI:10.1001/jama.291.14.1701]

- Arnold, J. D., Sarkodie, E. P., Coleman, M. E., & Goldstein, D. A. (2016). Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism in Transgender Women Receiving Oral Estradiol. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(11), 1773–1777. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.09.001]

- Asscheman, H., Gooren, L., & Eklund, P. (1989). Mortality and morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender hormone treatment. Metabolism, 38(9), 869–873. [DOI:10.1016/0026-0495(89)90233-3]

- Asscheman, H., Giltay, E. J., Megens, J. A., de Ronde, W. (Pim), van Trotsenburg, M. A., & Gooren, L. J. (2011). A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. European Journal of Endocrinology, 164(4), 635–642. [DOI:10.1530/eje-10-1038]

- Asscheman, H., T’Sjoen, G., Lemaire, A., Mas, M., Meriggiola, M. C., Mueller, A., Kuhn, A., Dhejne, C., Morel-Journel, N., & Gooren, L. J. (2013). Venous thrombo-embolism as a complication of cross-sex hormone treatment of male-to-female transsexual subjects: a review. Andrologia, 46(7), 791–795. [DOI:10.1111/and.12150]

- Baber, R. J., Panay, N., & Fenton, A. (2016). 2016 IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric, 19(2), 109–150. [DOI:10.3109/13697137.2015.1129166]

- Back, D. J., & Rogers, S. M. (1987). Review: first-pass metabolism by the gastrointestinal mucosa. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 1(5), 339–357. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2036.1987.tb00634.x]

- Bagot, C., Marsh, M., Whitehead, M., Sherwood, R., Roberts, L., Patel, R., & Arya, R. (2010). The effect of estrone on thrombin generation may explain the different thrombotic risk between oral and transdermal hormone replacement therapy. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 8(8), 1736–1744. [DOI:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03953.x]

- Bagot, C., Leishman, E., Onyiaodike, C., Jordan, F., Gibson, V., & Freeman, D. (2019). Changes in laboratory markers of thrombotic risk early in the first trimester of pregnancy may be linked to an increase in estradiol and progesterone. Thrombosis Research, 178, 47–53. [DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2019.03.015]

- Baron, J. A., Gridley, G., Weiderpass, E., Nyren, O., & Linet, M. (1998). Venous thromboembolism and cancer. The Lancet, 351(9109), 1077–1080. [DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(97)10018-6]

- Bezwada, P., Shaikh, A., & Misra, D. (2017). The Effect of Transdermal Estrogen Patch Use on Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Women’s Health, 26(12), 1319–1325. [DOI:10.1089/jwh.2016.6151]

- Blanco-Molina, M., Lozano, M., Cano, A., Cristobal, I., Pallardo, L., & Lete, I. (2012). Progestin-only contraception and venous thromboembolism. Thrombosis Research, 129(5), e257–e262. [DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2012.02.042]

- Bland, L. B., Garzotto, M., DeLoughery, T. G., Ryan, C. W., Schuff, K. G., Wersinger, E. M., Lemmon, D., & Beer, T. M. (2005). Phase II study of transdermal estradiol in androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 103(4), 717–723. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.20857]

- Blasdel, G., Shakir, N., Parker, A., Bluebond-Langner, R., & Zhao, L. (2021). Letter to the Editor from Blasdel et al: “No Venous Thromboembolism Increase Among Transgender Female Patients Remaining on Estrogen for Gender-affirming Surgery”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 106(9), e3783–e3784. [DOI:10.1210/clinem/dgab243]

- Blondon, M. (2020). Update On Oral Contraception And Venous Thromboembolism. HemaSphere Educational Updates in Hematology Book: 25th Congress of the European Hematology Association, Virtual Edition 2020, 4(S2). European Hematology Association. [Google 学术] [DOI:10.1097/HS9.0000000000000444] [PDF]

- Boskey, E. R., Taghinia, A. H., & Ganor, O. (2019). Association of Surgical Risk With Exogenous Hormone Use in Transgender Patients. JAMA Surgery, 154(2), 159–169. [DOI:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4598]

- Byar, D. P. (1973). The veterans administration cooperative urological research group’s studies of cancer of the prostate. Cancer, 32(5), 1126–1130. [DOI:10.1002/1097-0142(197311)32:5<1126::aid-cncr2820320518>3.0.co;2-c]

- Canonico, M., Plu-Bureau, G., Lowe, G. D., & Scarabin, P. (2008). Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 336(7655), 1227–1231. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.39555.441944.be]

- Canonico, M., Plu-Bureau, G., O’Sullivan, M. J., Stefanick, M. L., Cochrane, B., Scarabin, P., & Manson, J. E. (2014). Age at menopause, reproductive history, and venous thromboembolism risk among postmenopausal women. Menopause, 21(3), 214–220. [DOI:10.1097/gme.0b013e31829752e0]

- Cassidy, A., & Minihane, A. (2017). The role of metabolism (and the microbiome) in defining the clinical efficacy of dietary flavonoids. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 105(1), 10–22. [DOI:10.3945/ajcn.116.136051]

- Chaireti, R., Gustafsson, K. M., Bystrom, B., Bremme, K., & Lindahl, T. L. (2013). Endogenous thrombin potential is higher during the luteal phase than during the follicular phase of a normal menstrual cycle. Human Reproduction, 28(7), 1846–1852. [DOI:10.1093/humrep/det092]

- Choi, J., Kim, D., Park, S., Lee, H., Kim, K., Kim, K., Kim, M., Kim, S., & Kim, S. (2015). Anti-thrombotic effect of rutin isolated from Dendropanax morbifera Leveille. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 120(2), 181–186. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.12.012]

- Cleuren, A., Van der Linden, I., de Visser, Y., Wagenaar, G., Reitsma, P., & van Vlijmen, B. (2010). 17α‐Ethinylestradiol rapidly alters transcript levels of murine coagulation genes via estrogen receptor α. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 8(8), 1838–1846. [DOI:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03930.x]

- Coelingh Bennink, H. J., Verhoeven, C., Dutman, A. E., & Thijssen, J. (2017). The use of high-dose estrogens for the treatment of breast cancer. Maturitas, 95, 11–23. [DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.10.010]

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … & Zucker, K. (2012). [World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)] Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. [DOI:10.1080/15532739.2011.700873] [网址] [PDF]

- Conard, J., Plu-Bureau, G., Bahi, N., Horellou, M., Pelissier, C., & Thalabard, J. (2004). Progestogen-only contraception in women at high risk of venous thromboembolism. Contraception, 70(6), 437–441. [DOI:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.07.009]

- Connelly, P. J., Marie Freel, E., Perry, C., Ewan, J., Touyz, R. M., Currie, G., & Delles, C. (2019). Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy, Vascular Health and Cardiovascular Disease in Transgender Adults. Hypertension, 74(6), 1266–1274. [DOI:10.1161/hypertensionaha.119.13080]

- Connors, J. M., & Middeldorp, S. (2019). Transgender patients and the role of the coagulation clinician. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 17(11), 1790–1797. [DOI:10.1111/jth.14626]

- Curb, J. D., Prentice, R. L., Bray, P. F., Langer, R. D., Van Horn, L., Barnabei, V. M., Bloch, M. J., Cyr, M. G., Gass, M., Lepine, L., Rodabough, R. J., Sidney, S., Uwaifo, G. I., & Rosendaal, F. R. (2006). Venous Thrombosis and Conjugated Equine Estrogen in Women Without a Uterus. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(7), 772–772. [DOI:10.1001/archinte.166.7.772]

- Cushman, M. (2004). Estrogen Plus Progestin and Risk of Venous Thrombosis. JAMA, 292(13), 1573–1580. [DOI:10.1001/jama.292.13.1573]

- d’Arcangues et al. (2003). Comparative study of the effects of two once-a-month injectable contraceptives (Cyclofem® and Mesigyna®) and one oral contraceptive (Ortho-Novum 1/35®) on coagulation and fibrinolysis. Contraception, 68(3), 159–176. [DOI:10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00164-1]

- Deitcher, S. R., & Gomes, M. P. (2004). The risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with adjuvant hormone therapy for breast carcinoma. Cancer, 101(3), 439–449. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.20347]

- DeLoughery, T. G. (2011). Estrogen and thrombosis: Controversies and common sense. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 12(2), 77–84. [DOI:10.1007/s11154-011-9178-0]

- Deutsch, M. B. (2016). Overview of feminizing hormone therapy. In Deutsch, M. B. (Ed.). Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People, 2nd Edition (pp. 26–48). San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco/UCSF Transgender Care. [网址] [PDF]

- Dinger, J., Do Minh, T., & Heinemann, K. (2016). Impact of estrogen type on cardiovascular safety of combined oral contraceptives. Contraception, 94(4), 328–339. [DOI:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.06.010]

- Dittrich, R., Binder, H., Cupisti, S., Hoffmann, I., Beckmann, M., & Mueller, A. (2005). Endocrine Treatment of Male-to-Female Transsexuals Using Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 113(10), 586–592. [DOI:10.1055/s-2005-865900]

- Douxfils, J., Morimont, L., & Bouvy, C. (2020). Oral Contraceptives and Venous Thromboembolism: Focus on Testing that May Enable Prediction and Assessment of the Risk. Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis, 46(8), 872–886. [DOI:10.1055/s-0040-1714140]

- Douxfils, J., Klipping, C., Duijkers, I., Kinet, V., Mawet, M., Maillard, C., Jost, M., Rosing, J., & Foidart, J. (2020). Evaluation of the effect of a new oral contraceptive containing estetrol and drospirenone on hemostasis parameters. Contraception, 102(6), 396–402. [DOI:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.08.015]

- Dutra, E., Lee, J., Torbati, T., Garcia, M., Merz, C. N., & Shufelt, C. (2019). Cardiovascular implications of gender-affirming hormone treatment in the transgender population. Maturitas, 129, 45–49. [DOI:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.08.010]

- Eilertsen, A. L., Dahm, A. E., Høibraaten, E., Lofthus, C. M., Mowinckel, M., & Sandset, P. M. (2019). Relationship between sex hormone binding globulin and blood coagulation in women on postmenopausal hormone treatment. Blood Coagulation & Fibrinolysis, 30(1), 17–23. [DOI:10.1097/mbc.0000000000000784]

- Eisenfeld, A. J., & Aten, R. F. (1979). Estrogen receptor in the mammalian liver. In Briggs, M. H., & Corbin, A. (Eds.). Advances in Steroid Biochemistry and Pharmacology, 7, 91–117. London: Academic Press. [Google 学术] [PubMed]

- Eisenfeld, A. J., & Aten, R. F. (1987). Estrogen receptors and androgen receptors in the mammalian liver. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 27(4–6), 1109–1118. [DOI:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90197-x]

- Fabian, C. J., & Kimler, B. F. (2005). Selective Estrogen-Receptor Modulators for Primary Prevention of Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(8), 1644–1655. [DOI:10.1200/jco.2005.11.005]

- Fåhraeus, L., & Larsson-Cohn, U. (1982). Oestrogens, gonadotrophins and SHBG during oral and cutaneous administration of oestradiol-17β to menopausal women. Acta Endocrinologica, 101(4), 592–596. [DOI:10.1530/acta.0.1010592]

- Feldman, J. L., & Goldberg, J. (2006). Transgender Primary Medical Care: Suggested Guidelines for Clinicians in British Columbia. crhc/csac/Transcend Transgender Support & Education Society/Vancouver Coastal Health. [Google 学术] [PDF] .

- Franchini, M., & Mannucci, P. M. (2015). Classic thrombophilic gene variants. Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 114(11), 885–889. [DOI:10.1160/th15-02-0141]

- Fruzzetti, F., & Cagnacci, A. (2018). Venous thrombosis and hormonal contraception: what’s new with estradiol-based hormonal contraceptives? Open Access Journal of Contraception, 9, 75–79. [DOI:10.2147/oajc.s179673]

- Gerstman, B. B., Piper, J. M., Tomita, D. K., Ferguson, W. J., Stadel, B. V., & Lundin, F. E. (1991). Oral Contraceptive Estrogen Dose and the Risk of Deep Venous Thromboembolic Disease. American Journal of Epidemiology, 133(1), 32–37. [DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115799]

- Getahun, D., Nash, R., Flanders, W. D., Baird, T. C., Becerra-Culqui, T. A., Cromwell, L., Hunkeler, E., Lash, T. L., Millman, A., Quinn, V. P., Robinson, B., Roblin, D., Silverberg, M. J., Safer, J., Slovis, J., Tangpricha, V., & Goodman, M. (2018). Cross-sex Hormones and Acute Cardiovascular Events in Transgender Persons. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(4), 205. [DOI:10.7326/m17-2785]

- Gibney, J., Johannsson, G., Leung, K., & Ho, K. K. (2005). Comparison of the Metabolic Effects of Raloxifene and Oral Estrogen in Postmenopausal and Growth Hormone-Deficient Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(7), 3897–3903. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2005-0173]

- Gilbert, D. C., Duong, T., Sydes, M., Bara, A., Clarke, N., Abel, P., James, N., Langley, R., Parmar, M., & (2018). Transdermal oestradiol as a method of androgen suppression for prostate cancer within the STAMPEDE trial platform. BJU International, 121(5), 680–683. [DOI:10.1111/bju.14153]

- Glintborg, D., T’Sjoen, G., Ravn, P., & Andersen, M. S. (2021). MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Optimal feminizing hormone treatment in transgender people. European Journal of Endocrinology, 185(2), R49–R63. [DOI:10.1530/eje-21-0059]

- Goldstein, Z., Khan, M., Reisman, T., & Safer, J. D. (2019). Managing the risk of venous thromboembolism in transgender adults undergoing hormone therapy. Journal of Blood Medicine, 10, 209–216. [DOI:10.2147/jbm.s166780]

- Gooren, L. J., & T’Sjoen, G. (2018). Endocrine treatment of aging transgender people. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 19(3), 253–262. [DOI:10.1007/s11154-018-9449-0]

- Gourdy, P., Bachelot, A., Catteau-Jonard, S., Chabbert-Buffet, N., Christin-Maître, S., Conard, J., Fredenrich, A., Gompel, A., Lamiche-Lorenzini, F., Moreau, C., Plu-Bureau, G., Vambergue, A., Vergès, B., & Kerlan, V. (2012). Hormonal contraception in women at risk of vascular and metabolic disorders: Guidelines of the French Society of Endocrinology. Annales d’Endocrinologie, 73(5), 469–487. [DOI:10.1016/j.ando.2012.09.001]

- Grady, D., Wenger, N. K., Herrington, D., Khan, S., Furberg, C., Hunninghake, D., Vittinghoff, E., Hulley, S., & (2000). Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy Increases Risk for Venous Thromboembolic Disease: The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 132(9), 689–696. [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00002]

- Grandi, G., Facchinetti, F., & Bitzer, J. (2017). Estradiol in hormonal contraception: real evolution or just same old wine in a new bottle? The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 22(4), 245–246. [DOI:10.1080/13625187.2017.1372571]

- Grandi, G., Barra, F., Ferrero, S., & Facchinetti, F. (2019). Estradiol in non-oral hormonal contraception: a “long and winding road”. Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism, 14(3), 153–155. [DOI:10.1080/17446651.2019.1604217]

- Grandi, G., Del Savio, M. C., Lopes da Silva-Filho, A., & Facchinetti, F. (2020). Estetrol (E4): the new estrogenic component of combined oral contraceptives. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 13(4), 327–330. [DOI:10.1080/17512433.2020.1750365]

- Grandi, G., Facchinetti, F., & Bitzer, J. (2022). Confirmation of the safety of combined oral contraceptives containing oestradiol on the risk of venous thromboembolism. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 27(2), 83–84. [DOI:10.1080/13625187.2022.2029397]

- Grossmann, M., Wierman, M. E., Angus, P., & Handelsman, D. J. (2018). Reproductive Endocrinology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Endocrine Reviews, 40(2), 417–446. [DOI:10.1210/er.2018-00158]

- Hammond, G. L. (2017). Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and the Metabolic Syndrome. In Winters, S. J., & Huhtaniemi, I. T. (Eds.). Male Hypogonadism: Basic, Clinical and Therapeutic Principles, 2nd Edition (pp. 305–324). Cham: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-53298-1_15]

- Hannaford, P. C., Iversen, L., Macfarlane, T. V., Elliott, A. M., Angus, V., & Lee, A. J. (2010). Mortality among contraceptive pill users: cohort evidence from Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. BMJ, 340, c927. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.c927]

- Haupt, C., Henke, M., Kutschmar, A., Hauser, B., Baldinger, S., Saenz, S. R., & Schreiber, G. (2020). Antiandrogen or estradiol treatment or both during hormone therapy in transitioning transgender women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(11), CD013138. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.cd013138.pub2]

- Haveles, C. S., Wang, M. M., Arjun, A., Zaila, K. E., & Lee, J. C. (2020). Effect of Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy on Venous Thromboembolism Risk in Male-to-Female Gender-Affirming Surgery. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 86(1), 109–114. [DOI:10.1097/sap.0000000000002300]

- Hedlund, P. O., Johansson, R., Damber, J. E., Hagerman, I., Henriksson, P., Iversen, P., Klarskov, P., Mogensen, P., Rasmussen, F., & Varenhorst, E. (2011). Significance of pretreatment cardiovascular morbidity as a risk factor during treatment with parenteral oestrogen or combined androgen deprivation of 915 patients with metastasized prostate cancer: Evaluation of cardiovascular events in a randomized trial. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology, 45(5), 346–353. [DOI:10.3109/00365599.2011.585820]

- Heit, J. A., Silverstein, M. D., Mohr, D. N., Petterson, T. M., O’Fallon, W. M., & Melton, L. J. (2000). Risk Factors for Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160(6), 809–815. [DOI:10.1001/archinte.160.6.809]

- Heit, J. A., Spencer, F. A., & White, R. H. (2016). The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis, 41(1), 3–14. [DOI:10.1007/s11239-015-1311-6]

- Hembree, W. C., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Gooren, L., Hannema, S. E., Meyer, W. J., Murad, M. H., Rosenthal, S. M., Safer, J. D., Tangpricha, V., & T’Sjoen, G. G. (2017). Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 102(11), 3869–3903. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2017-01658]

- Hemelaar, M., van der Mooren, M. J., Rad, M., Kluft, C., & Kenemans, P. (2008). Effects of non-oral postmenopausal hormone therapy on markers of cardiovascular risk: a systematic review. Fertility and Sterility, 90(3), 642–672. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1298]

- Hibbs, D. (2008). Hormone replacement and the treatment of the transgender patient: A critical literature review. de Chesnay, M., & Anderson, B. (Eds.). Caring for the Vulnerable: Perspectives in Nursing Theory, Practice, and Research, 2nd Edition (pp. 351–362). Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones & Barlett. [Google 学术] [Google 阅读]

- Higdon, J., Drake, V. J., Delage, B., & Crozier, A. (2016). Flavonoids. Corvallis, Oregon: Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. [网址]

- Høibraaten, E., Qvigstad, E., Arnesen, H., Larsen, S., Wickstrøm, E., & Sandset, P. M. (2000). Increased Risk of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism during Hormone Replacement Therapy. Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 84(12), 961–967. [DOI:10.1055/s-0037-1614156]

- Høibraaten, E., Qvigstad, E., Andersen, T. O., Mowinckel, M., & Sandset, P. M. (2001). The Effects of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) on Hemostatic Variables in Women with Previous Venous Thromboembolism – Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Clinical Trial. Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 85(5), 775–781. [DOI:10.1055/s-0037-1615717]

- Holmegard, H., Nordestgaard, B., Schnohr, P., Tybjærg‐Hansen, A., & Benn, M. (2014). Endogenous sex hormones and risk of venous thromboembolism in women and men. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 12(3), 297–305. [DOI:10.1111/jth.12484]

- Hontscharuk, R., Alba, B., Manno, C., Pine, E., Deutsch, M. B., Coon, D., & Schechter, L. (2021). Perioperative Transgender Hormone Management: Avoiding Venous Thromboembolism and Other Complications. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, 147(4), 1008–1017. [DOI:10.1097/prs.0000000000007786]

- Hugon-Rodin, J., Alhenc-Gelas, M., Hemker, H. C., Brailly-Tabard, S., Guiochon-Mantel, A., Plu-Bureau, G., & Scarabin, P. (2016). Sex hormone-binding globulin and thrombin generation in women using hormonal contraception. Biomarkers, 22(1), 81–85. [DOI:10.1080/1354750x.2016.1204010]

- Hulley, S. (1998). Randomized Trial of Estrogen Plus Progestin for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease in Postmenopausal Women. JAMA, 280(7), 605–613. [DOI:10.1001/jama.280.7.605]

- Iqbal, J., Ginsburg, O. M., Wijeratne, T. D., Howell, A., Evans, G., Sestak, I., & Narod, S. A. (2012). Endometrial cancer and venous thromboembolism in women under age 50 who take tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 38(4), 318–328. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.06.009]

- Irwig, M. S. (2018). Cardiovascular health in transgender people. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 19(3), 243–251. [DOI:10.1007/s11154-018-9454-3]

- Iwamoto, S. J., Defreyne, J., Rothman, M. S., Van Schuylenbergh, J., Van de Bruaene, L., Motmans, J., & T’Sjoen, G. (2019). Health considerations for transgender women and remaining unknowns: a narrative review. Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 10, 204201881987116. [DOI:10.1177/2042018819871166]

- Jasuja, R., Passam, F. H., Kennedy, D. R., Kim, S. H., van Hessem, L., Lin, L., Bowley, S. R., Joshi, S. S., Dilks, J. R., Furie, B., Furie, B. C., & Flaumenhaft, R. (2012). Protein disulfide isomerase inhibitors constitute a new class of antithrombotic agents. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 122(6), 2104–2113. [DOI:10.1172/jci61228]

- Jensen, E. V., Jacobson, H. I., Walf, A. A., & Frye, C. A. (2010). Estrogen action: A historic perspective on the implications of considering alternative approaches. Physiology & Behavior, 99(2), 151–162. [DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.08.013]

- Kaemmle, L. M., Stadler, A., Janka, H., von Wolff, M., & Stute, P. (2022). The impact of micronized progesterone on cardiovascular events – a systematic review. Climacteric, 25(4), 327–336. [DOI:10.1080/13697137.2021.2022644]

- Kasum, M., Danolić, D., Orešković, S., Ježek, D., Beketić-Orešković, L., & Pekez, M. (2014). Thrombosis following ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Gynecological Endocrinology, 30(11), 764–768. [DOI:10.3109/09513590.2014.927858]

- Keenan, L., Kerr, T., Duane, M., & Van Gundy, K. (2018). Systematic Review of Hormonal Contraception and Risk of Venous Thrombosis. The Linacre Quarterly, 85(4), 470–477. [DOI:10.1177/0024363918816683]

- Kerlan, V., Nahoul, K., Martelot, M., & Bercovici, J. (1994). Longitudinal study of maternal plasma bioavailable testosterone and androstanediol glucuronide levels during pregnancy. Clinical Endocrinology, 40(2), 263–267. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02478.x]

- Khan, J., Schmidt, R. L., Spittal, M. J., Goldstein, Z., Smock, K. J., & Greene, D. N. (2019). Venous Thrombotic Risk in Transgender Women Undergoing Estrogen Therapy: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Clinical Chemistry, 65(1), 57–66. [DOI:10.1373/clinchem.2018.288316]

- Kitamura, T. (2001). Necessity of re‐evaluation of estramustine phosphate sodium (EMP) as a treatment option for first‐line monotherapy in advanced prostate cancer. International Journal of Urology, 8(2), 33–36. [DOI:10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00254.x]

- Klil-Drori, A. J., Yin, H., Tagalakis, V., Aprikian, A., & Azoulay, L. (2016). Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer and the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism. European Urology, 70(1), 56–61. [DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.022]

- Kohli, M., & McClellan, J. (2001). Parenteral Estrogen Therapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer: Retrospective Analysis of Intra-Muscular Estradiol Valerate in “Hormone Refractory” Prostate Disease. In Grunberg, S. M. (Ed.). Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology [Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol / Proceedings of ASCO], 20 [Thirty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 12–15, 2001, San Francisco, California], 164b–164b (abstract no. 2407). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [ISSN:1081-0641] [ISBN-10:0-9664495-3-3] [Google 学术] [OCLC:107121093] [OCLC:107121085] [OCLC:1132117477] [PDF]

- Kohli, M., Alikhan, M. A., Spencer, H. J., & Carter, G. (2004). Phase I trial of intramuscular estradiol valerate (I/M-E) in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(14 Suppl) [40th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: June 5–8, 2004, Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, Annual Meeting Proceedings], 436–436 (abstract no. 4726). [DOI:10.1200/jco.2004.22.90140.4726] [Google 阅读] [PDF]

- Kohli, M. (2006). Phase II study of transdermal estradiol in androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 106(1), 234–235. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.21528]

- Konkle, B. A., & Sood, S. L. (2019). Thrombotic Risk of Contraceptives and Other Hormonal Therapies. In Kitchens, C. S., Kessler, C. M., Konkle, B. A., Streiff, M. B., & Garcia, D. A. (Eds.). Consultative Hemostasis and Thrombosis, 4th Edition (pp. 637–650). Philadelphia: Elsevier. [DOI:10.1016/b978-0-323-46202-0.00031-5]

- Kotamarti, V. S., Greige, N., Heiman, A. J., Patel, A., & Ricci, J. A. (2021). Risk for Venous Thromboembolism in Transgender Patients Undergoing Cross-Sex Hormone Treatment: A Systematic Review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(7), 1280–1291. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.04.006]

- Kozato, A., Fox, G. W., Yong, P. C., Shin, S. J., Avanessian, B. K., Ting, J., Ling, Y., Karim, S., Safer, J. D., & Pang, J. H. (2021). No Venous Thromboembolism Increase Among Transgender Female Patients Remaining on Estrogen for Gender-Affirming Surgery. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 106(4), 1586–1590. [DOI:10.1210/clinem/dgaa966]

- Kronawitter, D., Gooren, L. J., Zollver, H., Oppelt, P. G., Beckmann, M. W., Dittrich, R., & Mueller, A. (2009). Effects of transdermal testosterone or oral dydrogesterone on hypoactive sexual desire disorder in transsexual women: results of a pilot study. European Journal of Endocrinology, 161(2), 363–368. [DOI:10.1530/eje-09-0265] [表格]

- Kuhl, H. (1990). Ovulationshemmer: Die Bedeutung der Östrogendosis. [Ovulation Preventives: The Significance of the Estrogen Dose. / Ovulation Inhibitors: The Significance of Estrogen Dose.] Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 50(12), 910–922. [Google 学术 1] [Google 学术 2] [PubMed] [DOI:10.1055/s-2008-1026392] [英译本]

- Kuhl, H. (1996). Effects of progestogens on haemostasis. Maturitas, 24(1–2), 1–19. [DOI:10.1016/0378-5122(96)00994-2]

- Kuhl, H. (1997). Metabolische Effekte der Östrogene und Gestagene. [Metabolic Effects of Estrogens and Progestogens.] Der Gynäkologe, 30(4), 357–369. [DOI:10.1007/pl00003042]

- Kuhl, H. (1998). Adverse effects of estrogen treatment: natural vs. synthetic estrogens. In Lippert, T. H., Mueck, A. O., & Ginsburg, J. (Eds.). Sex Steroids and the Cardiovascular System: The Proceedings of the 1st Interdisciplinary Workshop, Tuebingen, Germany, October 1996. Parthenon Publishing Group, New York, London (pp. 201–210). London/New York: Parthenon. [Google 学术] [Google 阅读] [PDF]

- Kuhl, H. (1999). Hormonal contraception. In Oettel, M., & Schillinger, E. (Eds.). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen (Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Volume 135, Part 2) (pp. 363–407). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-60107-1_18] [PDF]

- Kuhl, H. (2005). Pharmacology of Estrogens and Progestogens: Influence of Different Routes of Administration. Climacteric, 8(Suppl 1), 3–63. [DOI:10.1080/13697130500148875] [PDF]

- Kuhl, H., & Stevenson, J. (2006). The effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on estrogen-dependent risks and benefits – an attempt to interpret the Women’s Health Initiative results. Gynecological Endocrinology, 22(6), 303–317. [DOI:10.1080/09513590600717368]

- Langley, R. E., Cafferty, F. H., Alhasso, A. A., Rosen, S. D., Sundaram, S. K., Freeman, S. C., Pollock, P., Jinks, R. C., Godsland, I. F., Kockelbergh, R., Clarke, N. W., Kynaston, H. G., Parmar, M. K., & Abel, P. D. (2013). Cardiovascular outcomes in patients with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer treated with luteinising-hormone-releasing-hormone agonists or transdermal oestrogen: the randomised, phase 2 MRC PATCH trial (PR09). The Lancet Oncology, 14(4), 306–316. [DOI:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70025-1]

- Langley, R. E., Gilbert, D. C., Duong, T., Clarke, N. W., Nankivell, M., Rosen, S. D., Mangar, S., Macnair, A., Sundaram, S. K., Laniado, M. E., Dixit, S., Madaan, S., Manetta, C., Pope, A., Scrase, C. D., Mckay, S., Muazzam, I. A., Collins, G. N., Worlding, J., Williams, S. T., Paez, E., Robinson, A., McFarlane, J., Deighan, J. V., Marshall, J., Forcat, S., Weiss, M., Kockelbergh, R., Alhasso, A., Kynaston, H., & Parmar, M. (2021). Transdermal oestradiol for androgen suppression in prostate cancer: long-term cardiovascular outcomes from the randomised Prostate Adenocarcinoma Transcutaneous Hormone (PATCH) trial programme. The Lancet, 397(10274), 581–591. [DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00100-8] [PDF] [补充附录]

- Lax, E. (1987). Mechanisms of physiological and pharmacological sex hormone action on the mammalian liver. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 27(4–6), 1119–1128. [DOI:10.1016/0022-4731(87)90198-1]

- Lidegaard, Ø. (2014). Hormonal contraception, thrombosis and age. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 13(10), 1353–1360. [DOI:10.1517/14740338.2014.950654]

- Lijfering, W. M., Rosendaal, F. R., & Cannegieter, S. C. (2010). Risk factors for venous thrombosis - current understanding from an epidemiological point of view. British Journal of Haematology, 149(6), 824–833. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08206.x]

- Lim, H. Y., Leemaqz, S. Y., Torkamani, N., Grossmann, M., Zajac, J. D., Nandurkar, H., Ho, P., & Cheung, A. S. (2020). Global Coagulation Assays in Transgender Women on Oral and Transdermal Estradiol Therapy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 105(7), e2369–e2377. [DOI:10.1210/clinem/dgaa262]

- Luria, M. H. (1989). Estrogen and coronary arterial disease in men. International Journal of Cardiology, 25(2), 159–166. [DOI:10.1016/0167-5273(89)90102-2]

- Ma, Y., Zeng, M., Sun, R., & Hu, M. (2015). Disposition of Flavonoids Impacts their Efficacy and Safety. Current Drug Metabolism, 15(9), 841–864. [DOI:10.2174/1389200216666150206123719]

- Machin, N., & Ragni, M. V. (2020). Hormones and thrombosis: risk across the reproductive years and beyond. Translational Research, 225, 9–19. [DOI:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.06.011]

- Mammen, E. F. (1992). Coagulation Abnormalities in Liver Disease. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, 6(6), 1247–1257. [DOI:10.1016/s0889-8588(18)30273-9]

- Mantha, S., Karp, R., Raghavan, V., Terrin, N., Bauer, K. A., & Zwicker, J. I. (2012). Assessing the risk of venous thromboembolic events in women taking progestin-only contraception: a meta-analysis. BMJ, 345, e4944. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.e4944]

- Martinelli, I., Passamonti, S. M., & Bucciarelli, P. (2014). Thrombophilic states. In Biller, J., & Ferro, J. M. (Eds.). Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part II (Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Volume 120) (pp. 1061–1071). Philadelphia: Elsevier. [DOI:10.1016/b978-0-7020-4087-0.00071-1]

- Martinez-Zapata, M. J., Vernooij, R. W., Uriona Tuma, S. M., Stein, A. T., Moreno, R. M., Vargas, E., Capellà, D., & Bonfill Cosp, X. (2016). Phlebotonics for venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016(4), CD003229. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.cd003229.pub3]

- Matharu, G. S., Kunutsor, S. K., Judge, A., Blom, A. W., & Whitehouse, M. R. (2020). Clinical Effectiveness and Safety of Aspirin for Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis After Total Hip and Knee Replacement. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(3), 376–384. [DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.6108]

- McLintock, C. (2014). Thromboembolism in pregnancy: Challenges and controversies in the prevention of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism and management of anticoagulation in women with mechanical prosthetic heart valves. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(4), 519–536. [DOI:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.03.001]

- Mekaj, A., Mekaj, Y., & Daci, F. (2015). New insights into the mechanisms of action of aspirin and its use in the prevention and treatment of arterial and venous thromboembolism. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 11, 1449–1456. [DOI:10.2147/tcrm.s92222]

- Mellinger, G. T., Bailar, J. C., Arduino, L. J., & the Veterans Administration Cooperative Urological Research Group. (1967). Treatment and survival of patients with cancer of the prostate. The Veterans Administration Co-operative Urological Research Group. Surgery Gynecology & Obstetrics, 124(5), 1011–1017. [Google 学术] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y., Jiang, H., Chen, A., Lu, F., Yang, H., Shen, M. Z., Sun, D., Shao, Q., & Fotherby, K. (1990). Hemostatic changes in women using a monthly injectable contraceptive for one year. Contraception, 42(4), 455–466. [DOI:10.1016/0010-7824(90)90052-w]

- Mikkola, A., Ruutu, M., Aro, J., Rannikko, S., & Salo, J. (1999). The role of parenteral polyestradiol phosphate in the treatment of advanced prostatic cancer on the threshold of the new millennium. Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae, 88(1), 18–21. [Google 学术] [PubMed] [PDF]

- Min, L. L., & Hopkins, R. (2021). Endocrinological Care for Patients Undergoing Gender Affirmation (Including Risk of Thromboembolic Events). In Nikolavsky, D., & Blakely, S. A. (Eds.). Urological Care for the Transgender Patient: A Comprehensive Guide (pp. 23–36). Cham: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-18533-6_3]

- Mohammed, K., Abu Dabrh, A. M., Benkhadra, K., Al Nofal, A., Carranza Leon, B. G., Prokop, L. J., Montori, V. M., Faubion, S. S., & Murad, M. H. (2015). Oral vs Transdermal Estrogen Therapy and Vascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 100(11), 4012–4020. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2015-2237]

- Montagnana, M., Favaloro, E. J., Franchini, M., Guidi, G. C., & Lippi, G. (2009). The role of ethnicity, age and gender in venous thromboembolism. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis, 29(4), 489–496. [DOI:10.1007/s11239-009-0365-8]

- Moores, L., Bilello, K. L., & Murin, S. (2004). Sex and gender issues and venous thromboembolism. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 25(2), 281–297. [DOI:10.1016/j.ccm.2004.01.013]

- Morimont, L., Dogné, J., & Douxfils, J. (2020). Letter to the Editors-in-Chief in response to the article of Abou-Ismail, et al. entitled “Estrogen and thrombosis: A bench to bedside review” (Thrombosis Research 192 (2020) 40–51). Thrombosis Research, 193, 221–223. [DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.08.006]

- Morimont, L., Haguet, H., Dogné, J., Gaspard, U., & Douxfils, J. (2021). Combined Oral Contraceptives and Venous Thromboembolism: Review and Perspective to Mitigate the Risk. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 12, 769187. [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2021.769187]

- Morling, J. R., Broderick, C., Yeoh, S. E., & Kolbach, D. N. (2018). Rutosides for treatment of post-thrombotic syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(11), CD005625. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.cd005625.pub4]

- Mueller, A., Dittrich, R., Binder, H., Kuehnel, W., Maltaris, T., Hoffmann, I., & Beckmann, M. W. (2005). High dose estrogen treatment increases bone mineral density in male-to-female transsexuals receiving gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in the absence of testosterone. European Journal of Endocrinology, 153(1), 107–113. [DOI:10.1530/eje.1.01943]

- Mueller, A., Binder, H., Cupisti, S., Hoffmann, I., Beckmann, M., & Dittrich, R. (2006). Effects on the Male Endocrine System of Long-term Treatment with Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone Agonists and Estrogens in Male-to-Female Transsexuals. Hormone and Metabolic Research, 38(3), 183–187. [DOI:10.1055/s-2006-925198]

- Mueller, A., Zollver, H., Kronawitter, D., Oppelt, P. G., Claassen, T., Hoffmann, I., Beckmann, M. W., & Dittrich, R. (2011). Body composition and bone mineral density in male-to-female transsexuals during cross-sex hormone therapy using gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 119(2), 95–100. [DOI:10.1055/s-0030-1255074] [表格]

- Nachtigall, L. E., Raju, U., Banerjee, S., Wan, L., & Levitz, M. (2000). Serum Estradiol-Binding Profiles in Postmenopausal Women Undergoing Three Common Estrogen Replacement Therapies. Menopause, 7(4), 243–250. [DOI:10.1097/00042192-200007040-00006]

- Nelson, M. D., Szczepaniak, L. S., Wei, J., Szczepaniak, E., Sánchez, F. J., Vilain, E., Stern, J. H., Bergman, R. N., Bairey Merz, C. N., & Clegg, D. J. (2016). Transwomen and the Metabolic Syndrome: Is Orchiectomy Protective? Transgender Health, 1(1), 165–171. [DOI:10.1089/trgh.2016.0016]

- Nolan, B. J., & Cheung, A. S. (2020). Estradiol Therapy in the Perioperative Period: Implications for Transgender People Undergoing Feminizing Hormone Therapy. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 93(4), 539–548. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nolan, B. J., & Cheung, A. S. (2021). Relationship Between Serum Estradiol Concentrations and Clinical Outcomes in Transgender Individuals Undergoing Feminizing Hormone Therapy: A Narrative Review. Transgender Health, 6(3), 125–131. [DOI:10.1089/trgh.2020.0077]

- Nolan, I. T., Haley, C., Morrison, S. D., Pannucci, C. J., & Satterwhite, T. (2021). Estrogen Continuation and Venous Thromboembolism in Penile Inversion Vaginoplasty. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(1), 193–200. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.10.018]

- Ockrim, J., & Abel, P. D. (2009). Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer – the potential of parenteral estrogen. Central European Journal of Urology, 62, 132–140. [DOI:10.5173/ceju.2009.03.art1]

- Odlind, V., Milsom, I., Persson, I., & Victor, A. (2002). Can changes in sex hormone binding globulin predict the risk of venous thromboembolism with combined oral contraceptive pills?: A discussion based on recent recommendations from the European agency for evaluation of medicinal products regarding third generation oral contraceptive pills. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 81(6), 482–490. [DOI:10.1080/j.1600-0412.2002.810603.x] [网址]

- Oger, E., & (2000). Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism: A Community-based Study in Western France. Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 83(5), 657–660. [DOI:10.1055/s-0037-1613887]

- Ohlander, S. J., Varghese, B., & Pastuszak, A. W. (2018). Erythrocytosis Following Testosterone Therapy. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 6(1), 77–85. [DOI:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.04.001]

- Olié, V., Canonico, M., & Scarabin, P. (2010). Risk of venous thrombosis with oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy among postmenopausal women. Current Opinion in Hematology, 17(5), 457–463. [DOI:10.1097/moh.0b013e32833c07bc]

- Olié, V., Plu-Bureau, G., Conard, J., Horellou, M., Canonico, M., & Scarabin, P. (2011). Hormone therapy and recurrence of venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women. Menopause, 18(5), 488–493. [DOI:10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f9f7c3]

- Oliver-Williams, C., Glisic, M., Shahzad, S., Brown, E., Pellegrino Baena, C., Chadni, M., Chowdhury, R., Franco, O. H., & Muka, T. (2018). The route of administration, timing, duration and dose of postmenopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular outcomes in women: a systematic review. Human Reproduction Update, 25(2), 257–271. [DOI:10.1093/humupd/dmy039]

- Olov Hedlund, P., Damber, J., Hagerman, I., Haukaas, S., Henriksson, P., Iversen, P., Johansson, R., Klarskov, P., Lundbeck, F., Rasmussen, F., Varenhorst, E., Viitanen, J., Olov Hedlund, P., Damber, J., Hagerman, I., Haukaas, S., Henriksson, P., Iversen, P., Johansson, R., Klarskov, P., Lundbeck, F., Rasmussen, F., Varenhorst, E., Viitanen, J., & The SPCG-5 Study Group. (2008). Parenteral estrogen versus combined androgen deprivation in the treatment of metastatic prostatic cancer: Part 2. Final evaluation of the Scandinavian Prostatic Cancer Group (SPCG) Study No. 5. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology, 42(3), 220–229. [DOI:10.1080/00365590801943274]

- Park, W. (2002). Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMS) and their roles in breast cancer prevention. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 8(2), 82–88. [DOI:10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02282-7]

- Patel, K. T., Adeel, S., Rodrigues Miragaya, J., & Tangpricha, V. (2022). Progestogen Use in Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy: A Systematic Review. Endocrine Practice, 28(12), 1244–1252. [DOI:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.08.012]

- Peck-Radosavljevic, M. (2007). Review article: coagulation disorders in chronic liver disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 26, 21–28. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03509.x]

- Pfeifer, S., Butts, S., Dumesic, D., Fossum, G., Gracia, C., La Barbera, A., Mersereau, J., Odem, R., Penzias, A., Pisarska, M., Rebar, R., Reindollar, R., Rosen, M., Sandlow, J., Sokol, R., Vernon, M., & Widra, E. (2017). Combined hormonal contraception and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a guideline. Fertility and Sterility, 107(1), 43–51. [DOI:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.027]

- Phillips, I., Shah, S. I., Duong, T., Abel, P., & Langley, R. E. (2014). Androgen Deprivation Therapy and the Re-emergence of Parenteral Estrogen in Prostate Cancer. Oncology & Hematology Review, 10(1), 42–47. [PubMed Central] [DOI:10.17925/ohr.2014.10.1.42] [网址]

- Plu-Bureau, G., Maitrot-Mantelet, L., Hugon-Rodin, J., & Canonico, M. (2013). Hormonal contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: An epidemiological update. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 27(1), 25–34. [DOI:10.1016/j.beem.2012.11.002]

- Pomp, E. R., Rosendaal, F. R., & Doggen, C. J. (2008). Smoking increases the risk of venous thrombosis and acts synergistically with oral contraceptive use. American Journal of Hematology, 83(2), 97–102. [DOI:10.1002/ajh.21059]

- Pond, S. M., & Tozer, T. N. (1984). First-Pass Elimination. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 9(1), 1–25. [DOI:10.2165/00003088-198409010-00001]