译者按

- 本次翻译系对早前译文的完全重制。在此感谢 Sue-e89893 早前的贡献。

- 因译者能力所限,部分术语及段落之翻译或有纰漏,烦请指正。(个别句子在中文语境中稍显冗余或有语病,亦略去。)

摘要

诸如睾酮、雌二醇等性激素,会与一些血蛋白结合,如白蛋白和性激素结合球蛋白(SHBG)。该结合过程会降低性激素的游离比例,从而使其生物活性减弱。因此,睾酮、雌二醇可影响到其自身的游离比例。

在通常生理条件下,由于睾酮、雌二醇会在肝脏内被大量灭活,故其对 SHBG 水平的影响较小;而一旦其水平变得很高,其将对 SHBG 水平产生明显影响。例如,妊娠期间,随着雌二醇水平的大幅升高(可达 100 倍),SHBG 水平的增幅也会高达 5-10 倍。SHBG 水平的大幅增加会显著抑制睾酮的生物活性,但对雌二醇的情况则不同。在妊娠后期,游离雌二醇比例仅有非孕期的约一半;而在雌二醇水平更低的妊娠早期,游离雌二醇比例的降幅则更小。

在女性化激素疗法当中,临床上常规的雌二醇水平(200 pg/mL 以下)只会使得 SHBG 对其游离比例的限制作用相当微弱。不过,口服雌二醇的情况比较特殊,其对 SHBG 之生成的作用要大于非口服形式,从而减弱其活性;无论如何,以上仅存于理论可能,迄今尚未有临床研究报告其相对于非口服形式的重大疗效差异。

对于顺性别女性和女性倾向跨性别者,尽管 SHBG 可能会在某些情形下降低游离雌二醇比例,但要促成最大程度的女性化及乳房发育效果所需的雌二醇水平其实是很低的(50 pg/mL 以下)。综上所述,在女性化激素治疗过程中,无需过多担心 SHBG 对雌二醇效力的影响。

性激素与血蛋白的结合

性激素会与血液中的血浆蛋白结合。对于雄激素与雌激素,其主要与白蛋白、性激素结合球蛋白(SHBG)进行结合。该结合过程会使得性激素无法与其靶细胞相互作用,即结合并激活靶细胞之受体(Hammond, 2016)。这是因为,血浆蛋白体积过大,亲脂性也很弱,无法穿过主要由脂质构成的细胞膜。故此,它们不可能离开血液循环而从毛细血管扩散出来,从而渗透到各组织或被细胞吸收;与其结合的性激素自然也不能接触到对应的靶细胞。综上,血浆蛋白结合过程会限制性激素的生物活性(Hammond, 2016)。

该结合过程也会使得性激素的生物半衰期延长;因为性激素的代谢及消除过程同样需要被细胞摄入,而其结合蛋白无法被摄入。

每个 SHBG 分子仅有一个性激素结合位点(Moore & Bulbrook, 1988),而白蛋白有六个可结合不同基质的位点(Pardridge, 1988)。雄激素与雌二醇对 SHBG 的亲和力较强,而对白蛋白的亲和力较弱(Moore & Bulbrook, 1988; Hammond, 2016);不过,白蛋白的水平相较 SHBG 要高几个数量级[微摩尔浓度(μM)单位对纳摩尔浓度(nM)单位],从而使得性激素对两种蛋白的结合比例相近(Hammond, 2016)。

雄激素对 SHBG 的亲和力要高于雌二醇等雌激素;雌二醇的亲和力仅有二氢睾酮(DHT)的约 10-20%、睾酮的约 33-50%(Anderson, 1974; Ojasoo & Raynaud, 1978; Pugeat, Dunn, Nisula, 1981)。

血液中的性激素绝大部分皆与血浆蛋白结合;无论任何时候,都有超过 97% 的睾酮、雌二醇与孕酮被结合(Strauss & FitzGerald, 2019)。未结合 的部分性激素(也被称为游离 性激素),可扩散到细胞当中,从而被认为具有生物活性(Hammond, 2016)。

激素的总和 水平包括了已结合与未结合(游离)之激素;激素的可利用 水平则包括游离激素与已结合于白蛋白的激素——由于性激素对白蛋白的亲和力较弱,其与之结合时可能仍具备一定的生物活性,也即“可被利用”(Nguyen et al., 2008)。不过,尚需更多研究来充分阐明与白蛋白结合的性激素之生物活性。

下表列出了经大致计算得到的,雌二醇、睾酮和 DHT 对白蛋白、SHBG 及皮质类固醇结合球蛋白(CBG)的结合比例——其中 CBG 仅与一小部分的雄激素结合,而不与雌二醇结合。

表 1:各性激素与血浆蛋白的结合比例(计算值)(Dunn, Nisula, & Rodbard, 1981):

| 性激素 | 组别 | 白蛋白 (%) | SHBG (%) | CBG (%) | 游离 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 雌二醇 | 妇女(卵泡期) | 60.8 | 37.3 | <0.1 | 1.81 |

| 妇女(黄体期) | 61.1 | 37.0 | <0.1 | 1.82 | |

| 妇女(妊娠期) | 11.7 | 87.8 | <0.1 | 0.49 | |

| 男性 | 78.0 | 19.6 | <0.1 | 2.32 | |

| 睾酮 | 妇女(卵泡期) | 30.4 | 66.0 | 2.26 | 1.36 |

| 妇女(黄体期) | 30.7 | 65.7 | 2.20 | 1.37 | |

| 妇女(妊娠期) | 3.60 | 95.4 | 0.82 | 0.23 | |

| 男性 | 49.9 | 44.3 | 3.56 | 2.23 | |

| DHT | 妇女(卵泡期) | 21.0 | 78.4 | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| 妇女(黄体期) | 21.3 | 78.1 | 0.12 | 0.48 | |

| 妇女(妊娠期) | 2.15 | 97.8 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |

| 男性 | 39.2 | 59.7 | 0.22 | 0.88 |

游离性激素水平及比例,多通过依据多项已发表研究的数据所构建、确立的数学模型,从性激素总和水平及白蛋白、SHBG、CBG 水平算得。这是因为,游离性激素水平通常很低[仅在皮摩尔浓度级(pM)范围],难以被常规验血手段检出。该计算结果并非完全准确,尽管与实际值基本相当(Rosner, 2015; Goldman et al., 2017; Handelsman, 2017; Keevil & Adaway, 2019)。因此,如果可能的话,直接测量的结果会更佳。

性激素对 SHBG 之生成的影响

血浆蛋白(如白蛋白与 SHBG)在肝脏合成并分泌至血液中。除了与 SHBG 结合,性激素还调节肝脏生成 SHBG,从而影响其结合特性。雄激素会减少 SHBG 的生成,而雌激素则增加之(Anderson, 1974; Moore & Bulbrook, 1988)。

例如,服用蛋白同化激素:司坦唑醇(一种人工合成的 DHT 衍生物),几天内便可将 SHBG 水平抑制达 63%(Krause et al., 2004)。如持续服用超大剂量的睾酮及其它蛋白同化激素,可将 SHBG 水平降低 90%(Ruokonen et al., 1985; Moore & Bulbrook, 1988)。

与此类似,一些具有较弱雄激素效力的合成孕酮制剂(如醋酸甲羟孕酮、炔诺酮和左炔诺孕酮),会减少 SHBG 的产生(Kuhl, 2005; Moore & Bulbrook, 1988);而超高剂量下的醋酸甲羟孕酮及醋酸甲地孕酮,已被报告可将 SHBG 水平降低至多约 50-90%(Heubner et al., 1987; Lundgren et al., 1990; Lundgren & Lønning, 1990)。

与上述相反的是,服用包含炔雌醇(EE;一种合成雌激素)与一种合成孕酮(有极低雄激素效力或抗雄激素效力)的复方避孕药,会使 SHBG 水平升高约 4 倍(Odlind et al., 2002)。高剂量的合成雌激素(如 EE、己烯雌酚等)可将 SHBG 水平升高至多 5-10 倍(von Schoultz et al., 1989)。

通常情况下,睾酮、DHT 与雌二醇会被肝脏大量灭活,其在该部位的效力也较弱。因此,其对 SHBG 之生成的影响,要远弱于合成激素药物。与此对应,在妇女的整个月经周期当中,即便在雌二醇水平大幅波动的情况下,SHBG 水平亦仅有小幅变化(Freymann et al., 1977b; Plymate et al., 1985; Schijf et al., 1993; Braunstein et al., 2011; Rothman et al., 2011; Fanelli et al., 2013; Rezaii et al., 2017)。在一项研究中,从卵泡期过渡到黄体期时,SHBG 水平增加了约 6-13%(即 2.9–5.3 nmol/L)。此外,在更年期,即使雌二醇水平急剧降低,SHBG 水平也仅降低少许(Burger et al., 2000; Guthrie et al., 2004)。还有,接受雌二醇治疗时,在特定情形下还会显著地影响 SHBG 及其它肝蛋白的生成(Kuhl, 1998)。这是因为:1) 口服雌二醇的使用,因肝脏的首过效应,其对雌激素相关的肝脏分泌活动造成的影响相较非口服形式会更大;2) 高剂量雌二醇的使用,例如使用注射剂时的通常剂量。

下表展示了来自各研究项目的,不同雌激素给药途径、剂量及类型下的 SHBG 增幅。

表 2:不同雌激素暴露量下的 SHBG 增幅:

| 雌激素形式 | 剂量 | 通常的雌二醇水平(1) | SHBG 倍数 | 数据来源 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 口服雌二醇 | 1 mg/天 | ~25 pg/mL | 1.6x | Kuhl (1998) |

| 2 mg/天 | ~50 pg/mL | 2.2x | Kuhl (1998) | |

| 4 mg/天 | ~100 pg/mL | 1.9-3.2x | Fåhraeus & Larsson-Cohn (1982); Gibney et al. (2005); Ropponen et al. (2005) | |

| 口服戊酸雌二醇(2) | 6 mg/天 | ~112.5 pg/mL | 3.0x | Dittrich et al. (2005) |

| 雌二醇贴片 | 50 μg/天 | ~50 pg/mL | 1.1x | Kuhl (2005) |

| 100 μg/天 | ~100 pg/mL | 1.2x | Shifren et al. (2008) | |

| 200 μg/天 | ~200 pg/mL | ~1.5x | Smith et al. (2019) | |

| 300 μg/天 | ~300 pg/mL | ~1.7x | Smith et al. (2019) | |

| 600 μg/天 | ~600 pg/mL | 2.3x | Bland et al. (2005) | |

| 十一酸雌二醇注射剂 | 100 mg/月 | ~550 pg/mL | 2.0x | Derra (1981) |

| 聚磷酸雌二醇注射剂 | 320 mg/月 | ~700 pg/mL | 1.7x | Stege et al. (1988) |

| 戊酸雌二醇注射剂 | 10 mg/十天 | 不定(较高) | 3.2x | Mueller et al. (2011) |

| 口服炔雌醇 | 10 μg/天 | - | 3.0x | Kuhl (1998) |

| 50 μg/天 | - | 4.0x | Kuhl (1997) | |

| 合成雌激素 | 很高 | - | 5-10x | von Schoultz et al. (1989) |

(1) 依据多个来源的估计值(例如维基百科; Aly, 2020)。

(2) 由于分子质量的不同,戊酸雌二醇所含雌二醇,相当于同等质量雌二醇的约 75%;因此,6 mg/天剂量的戊酸雌二醇相当于摄入 4.5 mg/天的雌二醇。

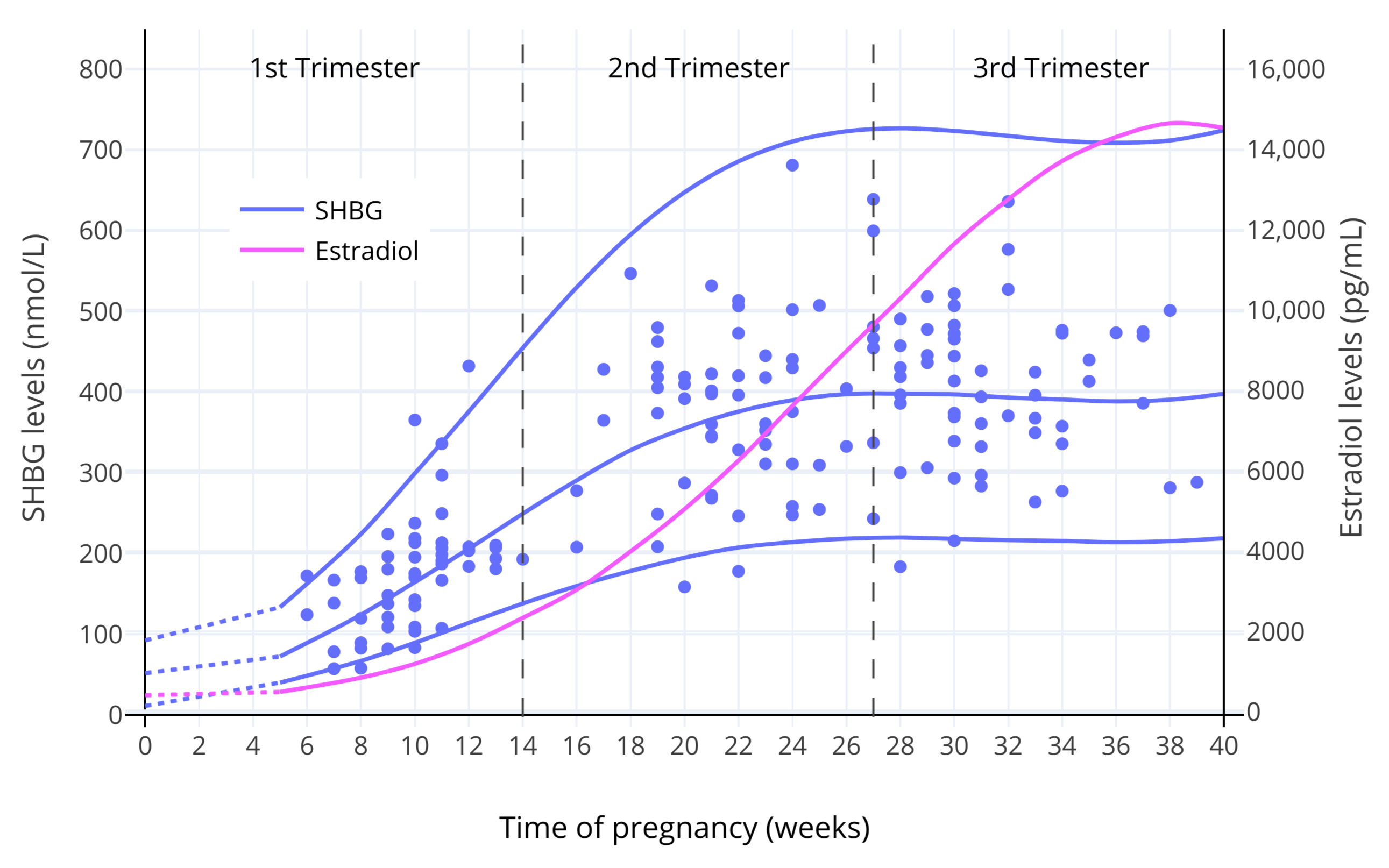

雌二醇对 SHBG 水平的影响与妊娠联系最密切,妊娠时雌二醇水平远高于正常值。在妊娠后期,雌二醇平均水平通常可达约 15000-25000 pg/mL(图表; Troisi et al., 2003; Adamcová et al., 2018);该值相当于正常月经周期内之水平的 100 倍左右。在雌二醇水平大幅上升的同时,SHBG 水平也升高约 5-10 倍(Anderson, 1974; Hammond, 2017)。

雌激素对 SHBG 之生成的剂量—反应曲线,显示了(SHBG 存在)饱和状态,表现在 SHBG 水平的升高多发生在雌二醇水平较低的区间、以及 SHBG 水平存在上限(Mean, Pellaton, & Magrini, 1977; O’Leary et al., 1991; Kerlan et al., 1994; Kuhl, 1999)。下图展示了妊娠期间 SHBG 水平的变化。

图 1:妊娠期间,SHBG 及总和雌二醇水平的变化(O’Leary et al., 1991)。其中,实线表示平均值/第 95 百分位数,而散点表示对各受试个体的测量值。

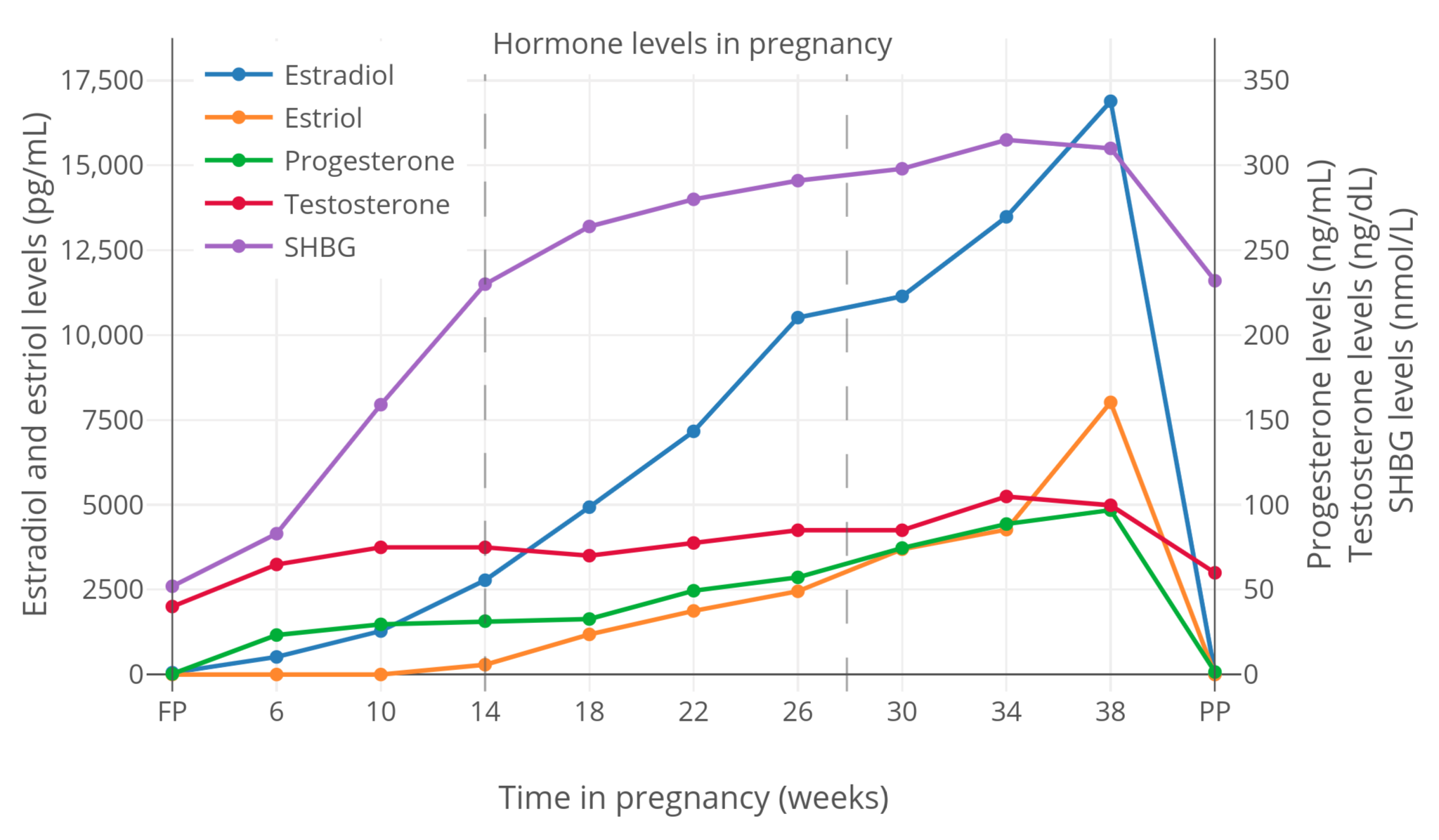

图 2:妊娠期间,SHBG 与性激素总和水平的变化(Kerlan et al., 1994)。

SHBG 水平之升高对游离性激素水平的影响

SHBG 水平的变化会引起与 SHBG 结合的性激素与游离性激素水平的改变。在这方面,除了 DHT 之外,雌二醇与睾酮是与之关联性最大的激素。

SHBG 水平之升高与游离睾酮的关系

含炔雌醇(EE)的避孕药,在将 SHBG 水平提升 4 倍的同时,会显著降低游离睾酮比例(Graham et al., 2007; Zimmerman et al., 2013)。在一项研究中,服用一片含 EE 的避孕药,可将游离睾酮比例从 2.45% 降至 0.78%(仅为前者的 32% 之多)(Graham et al., 2007)。由于其还可抑制睾酮生成、从而降低睾酮总和水平,故游离睾酮水平从 0.89 pg/mL 降至 0.18 pg/mL(仅为前者的 20% 之多)(Graham et al., 2007)。EE 对 SHBG 水平的影响,显著地增强了含 EE 的避孕药之抗雄效力,这也使得其被用于治疗女性痤疮及多毛症。

妊娠期间,睾酮水平可高达 150 ng/dL(约 5 倍于非孕期水平)(McClamrock, 2007)。妊娠期间 SHBG 生成的增多,在其对高水平的睾酮生物活性之中和上起到了重要作用(Hammond, 2017)。在一项研究中,妊娠后期的游离睾酮比例(0.23%)降至非孕期(1.36%)的 17%(Dunn, Nisula, & Rodbard, 1981)。因此,妊娠期间尽管有睾酮总和水平的大幅上升,但游离睾酮水平——或者说,体内雄激素作用——几乎不变(Barini, Liberale, & Menini, 1993; Schuijt et al., 2019)。一例由 SHBG 严重不足引起高雄激素血症的孕妇病例,证实了妊娠期 SHBG 对睾酮的雄激素活性之抑制作用(Hogeveen et al., 2002; Hammond, 2017)。

SHBG 水平之升高与游离雌二醇的关系

内源性与非口服形式的雌二醇

研究表明,在生理水平的雌二醇(如 200 pg/mL 以下)之下,SHBG 水平的增幅、以及游离雌二醇比例的降幅皆甚微。只要雌二醇来源并非口服,无论内源还是外源皆如此。这是由诸研究项目的游离雌二醇数据(通过计算或测量而得)所得出的结论(例如 Freymann et al., 1977b)。

不过,在超生理的雌二醇水平下(例如妊娠期间,或接受超高剂量雌二醇治疗时),SHBG 水平的增幅、以及游离雌二醇比例的降幅有所增大。迄今罕有针对高剂量雌二醇下游离雌二醇的改变而进行的研究。相较于计算结果,直接测量的游离雌二醇水平则愈发印证了这点。无论如何,如要观察高雌二醇水平下的游离雌二醇情况,不妨从妊娠入手;而且,妊娠期间极高的雌二醇水平会使得游离雌二醇更便于测量。相应地,已有多项对妊娠期游离雌二醇进行测量的研究公开发表。

妊娠期间,尽管游离雌二醇比例确实降低了,但增加的雌二醇远比被 SHBG 中和的要多;因此,游离雌二醇的情况与游离睾酮大相径庭。以下是一篇摘录对此的叙述(Rubinow et al., 2002):

血浆中许多甾体与多肽激素之水平随妊娠而缓慢、但持续地增长,而分娩后的几日内则骤降。当妊娠进入后三个月时,血浆孕酮水平平均在 150 ng/mL 左右,而雌二醇水平则达 10-15 ng/mL;其分别相当于月经周期内最大值的 10 倍和 50 倍(Tulchinsky et al., 1972)。妊娠期间,尽管这些甾体激素只有一小部分未被结合,但“游离”(即具备生物活性)的孕酮与雌激素总量仍大幅增加(Heidrich et al., 1994)。

该摘录引用了一项由 Heidrich 及其同行进行的研究,后者发现在分娩时,总雌二醇水平达 21,500 pg/mL,游离雌二醇水平则测得 232 pg/mL(占比约 1.08%)(Heidrich et al., 1994)。相比之下,非孕期妇女的游离雌二醇比例为 1.5-2.1%[经免疫测定法(RIA)测定];而其游离雌二醇水平则达 0.30-4.1 pg/mL(经 RIA 测定),或 0.40-5.9 pg/mL[经质谱测定法(MS)或液相色谱-质谱联用法(LC-MS)测定](Nakamoto, 2016)。因此,在此研究中的妊娠后期游离雌二醇水平,约为非孕期水平最大值的 50 倍。

因测定方法不同,来自单一研究的发现可能不具备代表性;故于下表列出取自多个项目的、妊娠后期游离雌二醇比例的测量值。

表 3:妊娠后期游离雌二醇比例的测量值(平均值 ± 标准差)(Perry et al., 1987):

| 研究项目 | 测量方法 | 采样次数 | 游离雌二醇 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perry et al. (1987) | 离心超滤法 | 25 | 1.27 ± 0.23 |

| Hammond et al. (1980) | 离心超滤法 | 5 | 0.96 ± 0.12 |

| Heidrich et al. (1994) | 离心超滤法 | 26 | 1.08 |

| Tulchinsky et al. (1973) | 平衡透析法 | 5 | 0.67 ± 0.18 |

| Freymann et al. (1977a) | 平衡透析法 | 17 | 1.15 |

| Anderson et al. (1985) | 稳态凝胶过滤法 | 12 | 1.48 ± 0.55 |

如上表所示,妊娠后期游离雌二醇比例约在 0.7-1.5% 之间。而经计算(而非测量)得出的结果,与测量值相近,不过有的显得略低(如 0.5%)(Dunn, Nisula, & Rodbard, 1981; Campino et al., 2001)。

这些测量值可与非孕期妇女的 1.5-2.1% 做审慎比较。如分别取中位数,则妊娠后期的游离雌二醇比例应大致为非孕期的 60%。此估计值与一项研究测量的实际结果(相比非孕期降至 55%)相当接近(Freymann et al., 1977a; Freymann et al., 1977b)。

雌酮、雌三醇的情况与雌二醇相反:其游离比例在妊娠后期与非孕期时并无区别(Tulchinsky & Chopra, 1973; Steingold et al., 1987);这是因为雌酮与雌三醇对 SHBG 的亲和度远低于雌二醇(Kuhl, 2005)。

一些研究也测定了妊娠早期的游离雌二醇比例——理论上妊娠早期的情况应与后期有异。下表列出了一项研究中对整个妊娠期内游离雌二醇测定的结果(Freymann et al., 1977a; Freymann et al., 1977b)。

图 4:妊娠期间雌二醇(E2)总和水平及游离水平的变化(平均值 ± 标准差)(Freymann et al., 1977a; Freymann et al., 1977b):

| 时间段 | 采样人次 | E2 (ng/mL) | 倍数 | 游离E2 (%) | 增幅 | 游离E2 (pg/mL) | 倍数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 非孕期 | 35 | 0.16 ± 0.10 | 1.0× | 2.2 ± 0.4 | –0% | 3.5 ± 2.0 | 1.0× |

| 妊娠 6-20 周 | 9 | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 13× | 1.6 ± 0.4 | –27% | 32 ± 21 | 9.1× |

| 妊娠 12–20 周 | 10 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 34× | 1.3 ± 0.3 | –41% | 72 ± 39 | 21× |

| 妊娠 20–30 周 | 12 | 10.8 ± 4.6 | 68× | 1.2 ± 0.3 | –45% | 130 ± 74 | 37× |

| 妊娠 30–38 周 | 17 | 16.0 ± 7.0 | 100× | 1.2 ± 0.2 | –45% | 184 ± 103 | 53× |

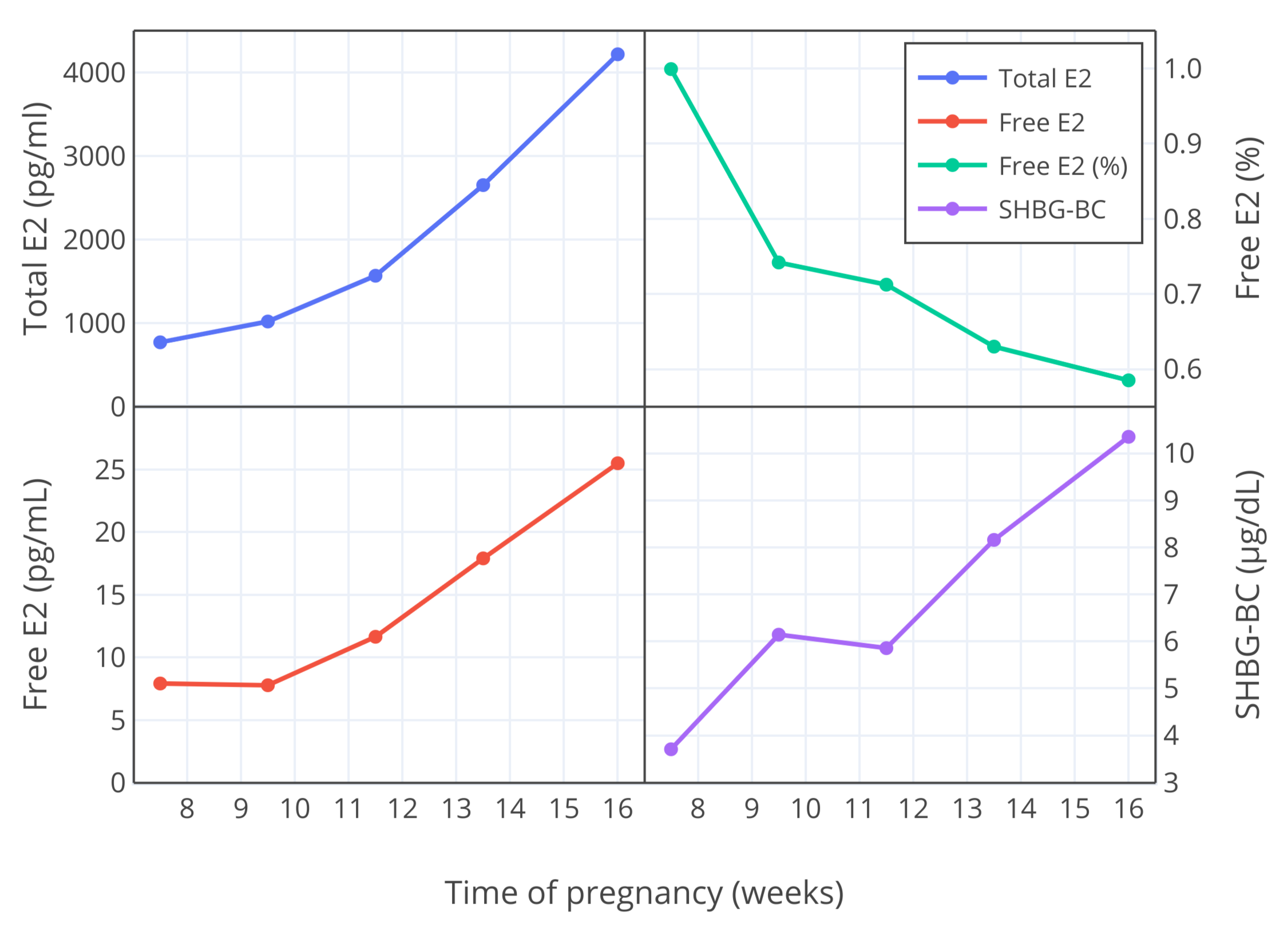

由另一研究者团队进行的研究,也测定了妊娠早期(7-16 周)的游离雌二醇比例,结果发现其低于 Freymann 及其同行的测量值;第 10 周的测量值约为 0.9-1.0%,到第 12 周则测得约 0.7%(Bernstein et al., 1986; Depue et al., 1987; Bernstein et al., 1988)。因此,与 Freymann 及其同行的结果相似,游离雌二醇比例随妊娠进行而降低。下图以可视化方式展示其发现。

图 3:妊娠第 7-16 周,雌二醇总和与游离水平 (pg/mL)、游离雌二醇比例 (%) 以及 SHBG 结合能力 (μg/dL) 的变化(Bernstein et al., 1986)。

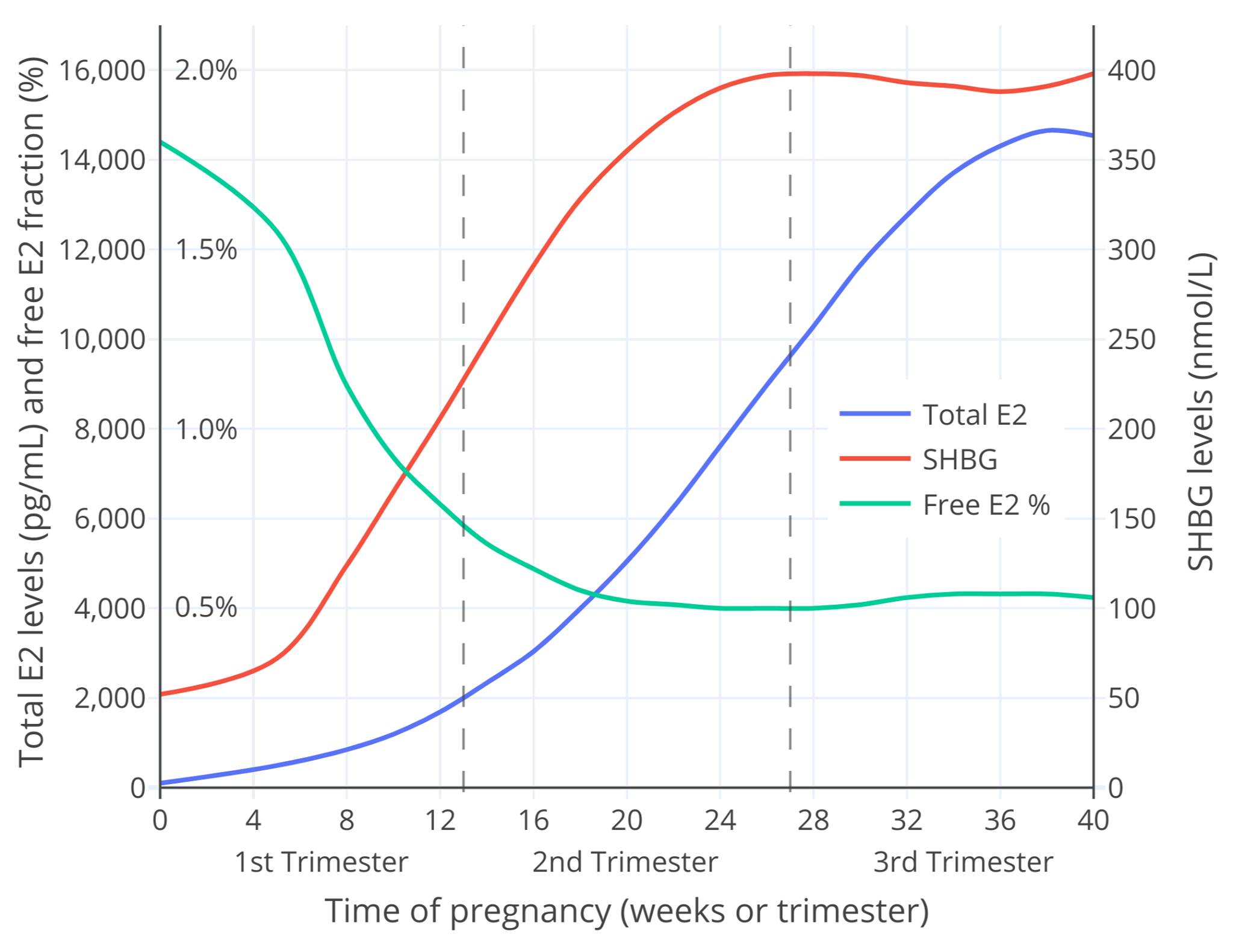

妊娠期游离雌二醇亦可通过雌二醇总和水平及 SHBG 水平计算得出。笔者使用 O’Leary 等人 (1991) 发表的数据与 Mazer (2009) 公开的电子表格计算器,粗略计算了妊娠期的游离雌二醇比例(Aly, 2020)。结果见下。

图 4:整个妊娠期当中的 SHBG 与雌二醇总和水平测量值,以及游离雌二醇比例计算值。

本图的另一个版本仅显示妊娠早期的变化(此时雌二醇水平通常不高于 2,000 pg/mL)。

图中的游离雌二醇比例仅为粗略估计,对此应有所保留。无论如何,其很接近于上文所讨论的研究项目对妊娠早期游离雌二醇的测量值——在数值上与 Bernstein 等人的相似,而在整个孕期的变化模式上则与 Bernstein 等人、Freymann 等人的相似。综上,此计算值所展现的模型不仅合理,也具有意义。

总的而言,妊娠期间雌二醇总和水平大幅上升,而 SHBG 水平也有较大提升(不过幅度相对较小);相应地,游离雌二醇比例随妊娠进行而逐渐降低。现有的研究就游离雌二醇比例降至何种程度尚存有分歧;但无论如何,到妊娠后期,该比例应该介于 0.5-1.5% 左右。该比例可与非孕期的游离雌二醇比例(1.5-2.1%)相比较,前者约为后者的 60%;极端情况下,该数字可达 25%。

与妊娠后期相反,在雌二醇水平更低的妊娠早期,游离雌二醇的比例会更高。

妊娠期间,尽管游离雌二醇比例降低了,但游离雌二醇水平随着总和雌二醇的大幅增加也有不小增长。由此可见,雌二醇水平的升高明显突破了与之一同上升的 SHBG 水平对其的限制作用。故此,妊娠会让人处于一种雌激素效力极高的状态。

妊娠期间,SHBG 对雌二醇的影响并不及对睾酮的那样,因为雌二醇水平的增长远大于 SHBG 的增长,而且雌二醇对 SHBG 的亲和力也不及睾酮。一般来说,与抑制睾酮的情况不同,要抑制随雌二醇水平大幅提高的雌二醇活性,则无疑需要极大提高 SHBG 的产量,而这是不可能的。

口服雌二醇

在游离雌二醇方面,口服雌二醇的表现或与非口服形式有所不同。这是因为,肝脏的首过效应会使其在肝脏中产生的雌二醇水平要高于血液中的水平,从而使得其对肝脏的效力与非口服形式不相称,SHBG 水平的增幅也更高。故此,口服雌二醇所引起的更高 SHBG 水平会导致游离雌二醇比例相较非口服形式更低。

如果要比较口服和非口服形式的雌二醇在游离雌二醇方面之差异,会发现测量其准确值变得愈发困难——不过这确实是可能的,迄今也有一些相关数据发表。一些有关更年期顺性别妇女使用低剂量口服雌二醇的临床研究称,SHBG 增加后对游离雌二醇(计算值)的限制作用较小(Nilsson, Holst, & von Schoultz, 1984; Nachtigall et al., 2000)。类似地,口服雌二醇对更年期症状显现的效果与非口服形式相近(维基百科; 见第二段)。

迄今罕有研究项目提供关于更高剂量的口服雌二醇所引起的 SHBG 或游离雌二醇水平数据;不过有这么一项研究,其发现跨性别女性使用 6 mg/天剂量的口服戊酸雌二醇(大致相当于 4.5 mg/天口服雌二醇),可将 SHBG 水平升高约 3.0 倍(Dittrich et al., 2005)。依据该项目有关总雌二醇与 SHBG 水平的数据,可以粗略计算(Mazer, 2009),其游离雌二醇比例应该从 2.1% 左右降至 1.2%(降幅达 43%)。与此类似,有一项研究使用了口服结合雌激素(CEE;“倍美力”),其剂量将 SHBG 水平升高了 2.3 倍;其也报告相较于同等剂量(即总雌二醇水平相当)的透皮雌二醇,游离雌二醇比例(计算值)要低出 40%(Shifren et al., 2007)。

以上发现表明,在女性倾向跨性别者通常使用的剂量下,口服雌二醇会降低游离雌二醇比例,且降幅不容忽视。所以,即使总雌二醇水平相当,口服雌二醇的效力可能也在某种程度上不及非口服形式。

不过需要明白,这一点尚未完全确定。在引起的雌酮水平上,口服雌二醇要远高于非口服形式(约 5 倍)(Kuhl, 2005),而雌酮尽管在效力上弱于雌二醇,但也有不小的、类似雌二醇的固有雌激素活性(Kuhl, 2005)。目前尚不明确雌酮会在多大程度上增强雌二醇的雌激素活性(如果有的话);不过,明显增强的可能性很高(Pande et al., 2019; 表格)。这样的话,额外的雌激素暴露量可能会弥补由口服雌二醇引起的高 SHBG 水平及较低游离雌二醇比例所造成的影响。然而,尚需更多研究来评估这一可能性。

此外还需留意,除游离雌二醇之外,口服雌二醇引起的高 SHBG 水平应该还会降低游离睾酮比例(而且降幅会更大)。这一点尤为重要,因为对于女性倾向跨性别者,对睾酮的压制是雌二醇疗效的关键一环,也是维持较高雌二醇水平的首要正当理由。基于上述可能性,以及激素游离水平仅可代表其理论生物活性的事实,不应想当然地认为口服雌二醇不及非口服形式有效。这个问题只能让对口服和非口服雌二醇做进一步比较的临床研究来解释了。

对女性化激素疗法的意义

有人担心,SHBG 会相当程度地限制雌二醇效力,从而对女性化/乳房发育过程造成阻碍。还有人声称,较高的雌二醇水平会引起 SHBG 的升高,从而会让其效力弱于较低雌二醇水平。然而,即使不考虑 SHBG 的情况,这些观点也很可能有误;这是因为,较低雌二醇水平(不足 50 pg/mL)已知足以在女性化和乳房发育方面产生完全效力。这点在经历正常或诱发的青春期的顺性别女孩(Aly, 2020)以及患有完全性雄激素不敏感综合征(CAIS)的、第二性征发育良好的女性身上被证实(Aly, 2020; 维基百科)。目前尚无证据表明,需要较高雌二醇水平以更好地促进女性化或乳房发育(Nolan & Cheung, 2020)。事实上,现有研究认为,临床上通常水平下的雌二醇(如 50-200 pg/mL)与女性倾向跨性别者的乳房发育不存在关联性(de Blok et al., 2017; Meyer et al., 2020; de Blok et al., 2020)。这与一项观点相契合:较低的雌二醇水平便已能够确保女性化及乳房发育效果最大化。因此,出于对雌激素暴露量不足、从而使女性化效果不完全的担忧,而使用高剂量雌二醇,是没有道理的;只当在需要压制睾酮的情况下才合乎情理。

不过,即使要深入探究 SHBG,现有研究表明 SHBG 在限制游离雌二醇——很可能也在限制雌二醇的生物活性——方面的作用也只能说有那么一些。在非孕期雌二醇的生理水平下(如 200 pg/mL 以下),由内源性及非口服形式的雌二醇引起的 SHBG 水平及游离雌二醇比例之变化微乎其微。然而,相当高的雌二醇水平对 SHBG 之生成的影响会更大。妊娠期内,随着大量增多的雌二醇而上升多达 5-10 倍的 SHBG 水平,会使游离雌二醇比例降至非孕期的 60%;但同时游离雌二醇的实际水平也会大幅上扬。而且,妊娠早期 SHBG 水平的增幅、以及游离雌二醇比例的降幅都要小于妊娠后期。

即使在非口服形式的雌二醇疗法所能达到的雌二醇水平最高位之下,由 SHBG 引起的游离雌二醇比例之降幅应该也很有限;仅需略为提高雌二醇剂量,便可覆盖其影响。

至于口服雌二醇,其情况则与上文不同:其对 SHBG 之生成的影响较非口服形式更大,SHBG 水平也更高,从而对游离雌二醇的限制作用更大。不过,目前有关这种游离雌二醇的降低会导致口服雌二醇的活性或效力减弱的说法仅存于理论可能。从疗效而言,口服雌二醇已经证明其自身非常有效;在低剂量下,游离雌二醇比例似乎降得并不多。此外,高剂量口服雌二醇对睾酮的压制作用,似乎与非口服形式相当——尽管尚无任何直接比较以佐证(维基百科; 图表)。除压制睾酮的效果外,现有研究并未发现口服与非口服形式雌二醇在女性化、乳房发育效果等方面有任何差异(Sam, 2020)。

综上,在 SHBG 水平及游离雌二醇比例方面,口服与非口服形式的雌二醇应该基本不存在疗效上的差别。

SHBG 水平的升高除了会降低游离雌二醇比例之外,还会降低游离睾酮比例,降幅亦更大。这点对女性倾向跨性别者很有利。

总而言之,在女性化激素治疗过程中,无需过多担心因 SHBG 升高引起的游离雌二醇比例降低的影响——无论使用口服还是非口服形式的雌二醇。

辅助阅读材料

本文的辅助阅读材料见此,其中有便于估算游离雌二醇水平的电子表格及其它计算器(如 Mazer, 2009)。

参考文献

- Adamcová, K., Kolátorová, L., Škodová, T., Šimková, M., Pařízek, A., Stárka, L., & Dušková, M. (2018). Steroid hormone levels in the peripartum period – differences caused by fetal sex and delivery type. Physiological Research, 67(Suppl 3), S489–S497. [DOI:10.33549/physiolres.934019]

- Anderson, D. C. (1974). Sex-Hormone-Binding Globulin. Clinical Endocrinology, 3(1), 69–96. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1974.tb03298.x]

- Anderson, P. J., Hancock, K. W., & Oakey, R. E. (1985). Non-protein-bound oestradiol and progesterone in human peripheral plasma before labour and delivery. Journal of Endocrinology, 104(1), 7–15. [DOI:10.1677/joe.0.1040007]

- Barini, A., Liberale, I., & Menini, E. (1993). Simultaneous Determination of Free Testosterone and Testosterone Bound to Non-Sex-Hormone-Binding Globulin by Equilibrium Dialysis. Clinical Chemistry, 39(6), 936–941. [DOI:10.1093/clinchem/39.6.936]

- Bernstein, L., Depue, R. H., Ross, R. K., Judd, H. L., Pike, M. C., & Henderson, B. E. (1986). Higher maternal levels of free estradiol in first compared to second pregnancy: early gestational differences. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 76(6), 1035–1039. [DOI:10.1093/jnci/76.6.1035]

- Bernstein, L., Pike, M., Depue, R., Ross, R., Moore, J., & Henderson, B. (1988). Maternal hormone levels in early gestation of cryptorchid males: a case-control study. British Journal of Cancer, 58(3), 379–381. [DOI:10.1038/bjc.1988.223]

- Bland, L. B., Garzotto, M., DeLoughery, T. G., Ryan, C. W., Schuff, K. G., Wersinger, E. M., Lemmon, D., & Beer, T. M. (2005). Phase II study of transdermal estradiol in androgen-independent prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 103(4), 717–723. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.20857]

- Braunstein, G. D., Reitz, R. E., Buch, A., Schnell, D., & Caulfield, M. P. (2011). Testosterone Reference Ranges in Normally Cycling Healthy Premenopausal Women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(10), 2924–2934. [DOI:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02380.x]

- Burger, H. G., Dudley, E. C., Cui, J., Dennerstein, L., & Hopper, J. L. (2000). A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Serum Testosterone, Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate, and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels through the Menopause Transition. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 85(8), 2832–2838. [DOI:10.1210/jcem.85.8.6740]

- Campino, C., Torres, C., Rioseco, A., Poblete, A., Pugin, E., Valdés, V., Catalán, S., Belmar, C., & Serón-Ferré, M. (2001). Plasma prolactin/oestradiol ratio at 38 weeks gestation predicts the duration of lactational amenorrhoea. Human Reproduction, 16(12), 2540–2545. [DOI:10.1093/humrep/16.12.2540]

- de Blok, C. J., Klaver, M., Wiepjes, C. M., Nota, N. M., Heijboer, A. C., Fisher, A. D., Schreiner, T., T’Sjoen, G., & den Heijer, M. (2017). Breast Development in Transwomen After 1 Year of Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(2), 532–538. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2017-01927]

- de Blok, C. J., Dijkman, B. A., Wiepjes, C. M., Staphorsius, A. S., Timmermans, F. W., Smit, J. M., Dreijerink, K. M., & den Heijer, M. (2020). Sustained Breast Development and Breast Anthropometric Changes in 3 Years of Gender-Affirming Hormone Treatment. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 106(2), e782–e790. [DOI:10.1210/clinem/dgaa841]

- Depue, R. H., Bernstein, L., Ross, R. K., Judd, H. L., & Henderson, B. E. (1987). Hyperemesis gravidarum in relation to estradiol levels, pregnancy outcome, and other maternal factors: A seroepidemiologic study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 156(5), 1137–1141. [DOI:10.1016/0002-9378(87)90126-8]

- Derra, C. (1981). Hormonprofile unter Östrogen- und Antiandrogentherapie bei Patienten mit Prostatakarzinom: Östradiolundecylat versus Cyproteronacetat. [Hormone Profiles under Estrogen and Antiandrogen Therapy in Patients with Prostate Cancer: Estradiol Undecylate versus Cyproterone Acetate.] (Doctoral dissertation, University of Mainz.) [Google 学术] [WorldCat] [PDF] [英译本]

- Dittrich, R., Binder, H., Cupisti, S., Hoffmann, I., Beckmann, M., & Mueller, A. (2005). Endocrine Treatment of Male-to-Female Transsexuals Using Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 113(10), 586–592. [DOI:10.1055/s-2005-865900]

- Dunn, J. F., Nisula, B. C., & Rodbard, D. (1981). Transport of Steroid Hormones: Binding of 21 Endogenous Steroids to Both Testosterone-Binding Globulin and Corticosteroid-Binding Globulin in Human Plasma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 53(1), 58–68. [DOI:10.1210/jcem-53-1-58]

- Fåhraeus, L., & Larsson-Cohn, U. (1982). Oestrogens, gonadotrophins and SHBG during oral and cutaneous administration of oestradiol-17β to menopausal women. Acta Endocrinologica, 101(4), 592–596. [DOI:10.1530/acta.0.1010592]

- Fanelli, F., Gambineri, A., Belluomo, I., Repaci, A., Di Lallo, V. D., Di Dalmazi, G., Mezzullo, M., Prontera, O., Cuomo, G., Zanotti, L., Paccapelo, A., Morselli-Labate, A. M., Pagotto, U., & Pasquali, R. (2013). Androgen Profiling by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in Healthy Normal-Weight Ovulatory and Anovulatory Late Adolescent and Young Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(7), 3058–3067. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2013-1381]

- Freymann, E., Hubl, W., Büchner, M., & Belleée, H. (1977). Eine spezifische, radioimmunologische Bestimmung des Plasmaöstradiols ohne Chromatographie im Zyklus und in der Schwangerschaft und die Bestimmung des freien, nichtproteingebundenen Anteils mittels Dialyse. [A specific radioimmunologi determination of plasma estradiol without chromatography during the cycle and in pregnancy and determination of the free non-protein-bound fraction using dialysis.] Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie, 99(6), 321–329. [Google 学术 1] [Google 学术 2] [PubMed] [PDF]

- Freymann, E., Hubl, W., Büchner, M., & Rohde, W. (1977). Plasma levels of apparent free estradiol during pregnancy. Endokrinologie, 69(2), 269–271. [Google 学术] [PubMed] [PDF]

- Gibney, J., Johannsson, G., Leung, K., & Ho, K. K. (2005). Comparison of the Metabolic Effects of Raloxifene and Oral Estrogen in Postmenopausal and Growth Hormone-Deficient Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(7), 3897–3903. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2005-0173]

- Goldman, A. L., Bhasin, S., Wu, F. C., Krishna, M., Matsumoto, A. M., & Jasuja, R. (2017). A Reappraisal of Testosterone’s Binding in Circulation: Physiological and Clinical Implications. Endocrine Reviews, 38(4), 302–324. [DOI:10.1210/er.2017-00025]

- Graham, C. A., Bancroft, J., Doll, H. A., Greco, T., & Tanner, A. (2007). Does oral contraceptive-induced reduction in free testosterone adversely affect the sexuality or mood of women? Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32(3), 246–255. [DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.12.011]

- Guthrie, J., Dennerstein, L., Taffe, J., Lehert, P., & Burger, H. (2004). The menopausal transition: a 9-year prospective population-based study. The Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project. Climacteric, 7(4), 375–389. [DOI:10.1080/13697130400012163]

- Hammond, G. L., Nisker, J. A., Jones, L. A., & Siiteri, P. K. (1980). Estimation of the percentage of free steroid in undiluted serum by centrifugal ultrafiltration-dialysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 255(11), 5023–5026. [DOI:10.1016/s0021-9258(19)70742-x]

- Hammond, G. L. (2016). Plasma steroid-binding proteins: primary gatekeepers of steroid hormone action. Journal of Endocrinology, 230(1), R13–R25. [DOI:10.1530/joe-16-0070]

- Hammond, G. L. (2017). Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin and the Metabolic Syndrome. In Winters, S. J., & Huhtaniemi, I. T. (Eds.). Male Hypogonadism: Basic, Clinical and Therapeutic Principles (pp. 305–324). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-53298-1_15]

- Handelsman, D. J. (2017). Free Testosterone: Pumping up the Tires or Ending the Free Ride? Endocrine Reviews, 38(4), 297–301. [DOI:10.1210/er.2017-00171]

- Heidrich, A., Schleyer, M., Spingler, H., Albert, P., Knoche, M., Fritze, J., & Lanczik, M. (1994). Postpartum blues: Relationship between not-protein bound steroid hormones in plasma and postpartum mood changes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 30(2), 93–98. [DOI:10.1016/0165-0327(94)90036-1]

- Heubner, A., Brockerhoff, P., Kreienberg, R., Grill, H., Rathgen, G., & Pollow, K. (1987). The influence of various dosages of megestrol acetate on SHBG, CBG and lipoprotein patterns. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 28(Suppl 1), 214S–214S (abstract no. 6). [DOI:10.1016/0022-4731(87)91680-3]

- Hogeveen, K. N., Cousin, P., Pugeat, M., Dewailly, D., Soudan, B., & Hammond, G. L. (2002). Human sex hormone-binding globulin variants associated with hyperandrogenism and ovarian dysfunction. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 109(7), 973–981. [DOI:10.1172/JCI14060]

- Keevil, B. G., & Adaway, J. (2019). Assessment of free testosterone concentration. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 190, 207–211. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.04.008]

- Kerlan, V., Nahoul, K., Martelot, M., & Bercovici, J. (1994). Longitudinal study of maternal plasma bioavailable testosterone and androstanediol glucuronide levels during pregnancy. Clinical Endocrinology, 40(2), 263–267. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2265.1994.tb02478.x]

- Krause, A., Sinnecker, G., Hiort, O., Thamm, B., & Hoepffner, W. (2004). Applicability of the SHBG Androgen Sensitivity Test in the Differential Diagnosis of 46,XY Gonadal Dysgenesis, True Hermaphroditism, and Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 112(5), 236–240. [DOI:10.1055/s-2004-817969]

- Kuhl, H. (1997). Metabolische Effekte der Östrogene und Gestagene. [Metabolic Effects of Estrogens and Progestogens.] Der Gynäkologe, 30(4), 357–369. [DOI:10.1007/pl00003042]

- Kuhl, H. (1998). Adverse effects of estrogen treatment: natural vs. synthetic estrogens. In Lippert, T. H., Mueck, A. O., & Ginsburg, J. (Eds.). Sex Steroids and the Cardiovascular System: The Proceedings of the 1st Interdisciplinary Workshop, Tuebingen, Germany, October 1996. Parthenon Publishing Group, New York, London (pp. 201–210). London/New York: Parthenon. [Google 学术] [Google 阅读] [PDF]

- Kuhl, H. (1999). Hormonal contraception. In Oettel, M., & Schillinger, E. (Eds.). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen (Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, Volume 135, Part 2) (pp. 363–407). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-60107-1_18] [PDF]

- Kuhl, H. (2005). Pharmacology of Estrogens and Progestogens: Influence of Different Routes of Administration. Climacteric, 8(Suppl 1), 3–63. [DOI:10.1080/13697130500148875] [PDF]

- Lundgren, S., Lønning, P., Utaaker, E., Aakvaag, A., & Kvinnsland, S. (1990). Influence of progestins on serum hormone levels in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer—I. General findings. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 36(1–2), 99–104. [DOI:10.1016/0022-4731(90)90118-c]

- Lundgren, S., & Lønning, P. (1990). Influence of progestins on serum hormone levels in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer—II. A differential effect of megestrol acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate on serum estrone sulfate and sex hormone binding globulin. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 36(1–2), 105–109. [DOI:10.1016/0022-4731(90)90119-d]

- Mazer, N. A. (2009). A novel spreadsheet method for calculating the free serum concentrations of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, estradiol, estrone and cortisol: With illustrative examples from male and female populations. Steroids, 74(6), 512–519. [DOI:10.1016/j.steroids.2009.01.008] [Excel 表格] [Google 表格]

- McClamrock, H. D. (2007). Pregnancy-Related Androgen Excess. In Azziz, R., Nestler, J. E., & Dewailly, D. (Eds.). Androgen Excess Disorders in Women: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Other Disorders, 2nd Edition (Contemporary Endocrinology) (pp. 107–119). Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press. [Google 阅读] [DOI:10.1007/978-1-59745-179-6_9]

- Mean, F., Pellaton, M., & Magrini, G. (1977). Study on the binding of dihydrotestosterone, testosterone and oestradiol with sex hormone binding globulin. Clinica Chimica Acta, 80(1), 171–180. [DOI:10.1016/0009-8981(77)90276-5]

- Meyer, G., Mayer, M., Mondorf, A., Flügel, A. K., Herrmann, E., & Bojunga, J. (2020). Safety and rapid efficacy of guideline-based gender-affirming hormone therapy: an analysis of 388 individuals diagnosed with gender dysphoria. European Journal of Endocrinology, 182(2), 149–156. [DOI:[10.1530/eje-19-0463][doi-b13bac6d]] [PDF]

- Moore, J. W., & Bulbrook, R. D. (1988). The epidemiology and function of sex hormone-binding globulin. Oxford Reviews of Reproductive Biology, 10, 180–236. [Google 学术] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A., Zollver, H., Kronawitter, D., Oppelt, P. G., Claassen, T., Hoffmann, I., Beckmann, M. W., & Dittrich, R. (2010). Body Composition and Bone Mineral Density in Male-to-Female Transsexuals During Cross-Sex Hormone Therapy Using Gonadotrophin-Releasing Hormone Agonist. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 119(2), 95–100. [DOI:10.1055/s-0030-1255074]

- Nachtigall, L. E., Raju, U., Banerjee, S., Wan, L., & Levitz, M. (2000). Serum Estradiol-Binding Profiles in Postmenopausal Women Undergoing Three Common Estrogen Replacement Therapies. Menopause, 7(4), 243–250. [DOI:10.1097/00042192-200007040-00006

- Nakamoto, J. (2016). Endocrine Testing. In Jameson, J. L., & De Groot, L. J. (Eds.). Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric, 7th Edition (pp. 2655–2688.e1). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. [Google 阅读] [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-323-18907-1.00154-2]

- Nguyen, T. D. T., Dolomie-Fagour, L., Georges, A., & Corcuff, J. B. (2008). Dosage des stéroïdes sexuels sériques: quelle place pour l’estradiol biodisponible? [What about bioavailable estradiol?] Annales de Biologie Clinique, 66(5), 493–497. [DOI:10.1684/abc.2008.0259]

- Nilsson, B., Holst, J., & Schoultz, B. (1984). Serum levels of unbound 17β-oestradiol during oral and percutaneous postmenopausal replacement therapy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 91(10), 1031–1036. [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb03683.x]

- Nolan, B. J., & Cheung, A. S. (2021). Relationship Between Serum Estradiol Concentrations and Clinical Outcomes in Transgender Individuals Undergoing Feminizing Hormone Therapy: A Narrative Review. Transgender Health, 6(3), 125–131. [DOI:10.1089/trgh.2020.0077]

- O’Leary, P., Boyne, P., Flett, P., Beilby, J., & James, I. (1991). Longitudinal assessment of changes in reproductive hormones during normal pregnancy. Clinical Chemistry, 37(5), 667–672. [DOI:10.1093/clinchem/37.5.667]

- Odlind, V., Milsom, I., Persson, I., & Victor, A. (2002). Can changes in sex hormone binding globulin predict the risk of venous thromboembolism with combined oral contraceptive pills? Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 81(6), 482–490. [DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810603.x]

- Ojasoo, T., & Raynaud, J. P. (1978). Unique steroid congeners for receptor studies. Cancer Research, 38(11 Part 2), 4186–4198. [Google 学术] [PubMed] [URL]

- Pande, P., Fleck, S. C., Twaddle, N. C., Churchwell, M. I., Doerge, D. R., & Teeguarden, J. G. (2019). Comparative estrogenicity of endogenous, environmental and dietary estrogens in pregnant women II: Total estrogenicity calculations accounting for competitive protein and receptor binding and potency. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 125, 341–353. [DOI:10.1016/j.fct.2018.12.013]

- Pardridge, W. M. (1988). Selective delivery of sex steroid hormones to tissues by albumin and by sex hormone-binding globulin. Oxford Reviews of Reproductive Biology, 10, 237–292. [Google 学术] [PubMed]

- Perry, L., Wathen, N., & Chard, T. (1987). Saliva Levels of Oestradiol and Progesterone in Relation to Non-Protein-Bound Concentrations in Blood During Late Pregnancy. Hormone and Metabolic Research, 19(9), 444–447. [DOI:10.1055/s-2007-1011848]

- Plymate, S. R., Moore, D. E., Cheng, C. Y., Bardin, C. W., Southworth, M. B., & Levinski, M. J. (1985). Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Changes during the Menstrual Cycle. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 61(5), 993–996. [DOI:10.1210/jcem-61-5-993]

- Pugeat, M. M., Dunn, J. F., & Nisula, B. C. (1981). Transport of Steroid Hormones: Interaction of 70 Drugs with Testosterone-Binding Globulin and Corticosteroid-Binding Globulin in Human Plasma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 53(1), 69–75. [DOI:10.1210/jcem-53-1-69]

- Rezaii, T., Gustafsson, T. P., Axelson, M., Zamani, L., Ernberg, M., Hirschberg, A. L., & Carlström, K. A. (2017). Circulating androgens and SHBG during the normal menstrual cycle in two ethnic populations. Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation, 77(3), 184–189. [DOI:10.1080/00365513.2017.1286685]

- Ropponen, A., Aittomäki, K., Vihma, V., Tikkanen, M. J., & Ylikorkala, O. (2005). Effects of Oral and Transdermal Estradiol Administration on Levels of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin in Postmenopausal Women with and without a History of Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 90(6), 3431–3434. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2005-0352]

- Rosner, W. (2015). Free estradiol and sex hormone-binding globulin. Steroids, 99, 113–116. [DOI:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.005]

- Rothman, M. S., Carlson, N. E., Xu, M., Wang, C., Swerdloff, R., Lee, P., Goh, V. H., Ridgway, E. C., & Wierman, M. E. (2011). Reexamination of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, estradiol and estrone levels across the menstrual cycle and in postmenopausal women measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Steroids, 76(1–2), 177–182. [DOI:10.1016/j.steroids.2010.10.010]

- Rubinow, D. R., Schmidt, P. J., Roca, C. A., & Daly, R. C. (2002). Gonadal Hormones and Behavior in Women: Concentrations versus Context. In Pfaff, D. W., Arnold, A. P., Etgen, A. M., Fahrbach, S. E., & Rubin, R. T. (Eds.). Hormones, Brain and Behavior, Volume 5 (pp. 37–73). Amsterdam: Academic Press. [Google 阅读] [DOI:10.1016/B978-012532104-4/50086-X]

- Ruokonen, A., Alén, M., Bolton, N., & Vihko, R. (1985). Response of serum testosterone and its precursor steroids, SHBG and CBG to anabolic steroid and testosterone self-administration in man. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 23(1), 33–38. [DOI:10.1016/0022-4731(85)90257-2]

- Schijf, C. P., van der Mooren, M. J., Doesburg, W. H., Thomas, C. M., & Rolland, R. (1993). Differences in serum lipids, lipoproteins, sex hormone binding globulin and testosterone between the follicular and the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Acta Endocrinologica, 129(2), 130–133. [DOI:10.1530/acta.0.1290130]

- Schuijt, M. P., Sweep, C. G., van der Steen, R., Olthaar, A. J., Stikkelbroeck, N. M., Ross, H. A., & van Herwaarden, A. E. (2019). Validity of free testosterone calculation in pregnant women. Endocrine Connections, 8(6), 672–679. [DOI:10.1530/ec-19-0110]

- Shifren, J. L., Desindes, S., McIlwain, M., Doros, G., & Mazer, N. A. (2007). A randomized, open-label, crossover study comparing the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen therapy on serum androgens, thyroid hormones, and adrenal hormones in naturally menopausal women. Menopause, 14(6), 985–994. [DOI:10.1097/gme.0b013e31803867a]

- Shifren, J. L., Rifai, N., Desindes, S., McIlwain, M., Doros, G., & Mazer, N. A. (2008). A Comparison of the Short-Term Effects of Oral Conjugated Equine Estrogens Versus Transdermal Estradiol on C-Reactive Protein, Other Serum Markers of Inflammation, and Other Hepatic Proteins in Naturally Menopausal Women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93(5), 1702–1710. [DOI:10.1210/jc.2007-2193]

- Smith, K., Galazi, M., Openshaw, M. R., Wilson, P., Sarker, S. J., O’Brien, N., Alifrangis, C., Stebbing, J., & Shamash, J. (2020). The Use of Transdermal Estrogen in Castrate-resistant, Steroid-refractory Prostate Cancer. Clinical Genitourinary Cancer, 18(3), e217–e223. [DOI:10.1016/j.clgc.2019.09.019]

- Stege, R., Carlström, K., Collste, L., Eriksson, A., Henriksson, P., & Pousette, A. (1988). Single drug polyestradiol phosphate therapy in prostatic cancer. American Journal of Clinical Oncology, 11(Suppl 2), S101–S103. [DOI:10.1097/00000421-198801102-00024] [PDF]

- Steingold, K. A., Pardridge, W. M., Judd, H. L., & Chaudhuri, G. (1987). The effects of membrane permeability and binding by human serum proteins on steroid influx into the rabbit uterus. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 157(6), 1543–1549. [DOI:10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80260-0]

- Strauss, J. F., & FitzGerald, G. A. (2019). Steroid Hormones and Other Lipid Molecules Involved in Human Reproduction. In Strauss, J. F., & Barbieri, R. L. (Eds.). Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, 8th Edition (pp. 75–114.e7). Philadelphia: Elsevier. [Google 阅读] [DOI:10.1016/b978-0-323-47912-7.00004-4]

- Troisi, R., Potischman, N., Roberts, J. M., Harger, G., Markovic, N., Cole, B., Lykins, D., Siiteri, P., & Hoover, R. N. (2003). Correlation of serum hormone concentrations in maternal and umbilical cord samples. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 12(5), 452–456. [Google 学术] [PubMed] [URL]

- Tulchinsky, D., & Chopra, I. J. (1973). Competitive Ligand-Binding Assay for Measurement of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG). The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 37(6), 873–881. [DOI:10.1210/jcem-37-6-873]

- von Schoultz, B., Carlström, K., Collste, L., Eriksson, A., Henriksson, P., Pousette, Å., & Stege, R. (1989). Estrogen therapy and liver function—metabolic effects of oral and parenteral administration. The Prostate, 14(4), 389–395. [DOI:10.1002/pros.2990140410]

- Zimmerman, Y., Eijkemans, M. J., Coelingh Bennink, H. J., Blankenstein, M. A., & Fauser, B. C. (2013). The effect of combined oral contraception on testosterone levels in healthy women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 20(1), 76–105. [DOI:10.1093/humupd/dmt038]

译文修订记录

| 日期 | 详情 |

|---|---|

| 2021 年 11 月 26 日 | 初次翻译。 |

| 2022 年 10 月 19 日 | 第一次修订,重新翻译了全文。 |

| 2023 年 3 月 15 日 | 第二次修订: 更新“摘要”一节和链接若干; 更正 progesterone(孕酮)的称谓; 增补“参考文献”及遗漏段落; 修复格式。 |

| 2023 年 6 月 29 日 | 更正“己烯雌酚”译名。 |